Historical background

Introduction

This chapter recounts in chronological order the socio-political developments of the Republican era. The narrative provides the background material necessary for the analysis that follows in later chapters. Interspersed within it is a parallel narrative, offering a very summary outline of the formative events in the history of the Gülen Movement. I shall point in particular to the ideas, attitudes and events of this period that have shaped and influenced the various kinds of mobilization in Turkey; the distinguishing characteristics of the socio-political context in which the Gülen Movement emerged and has worked; and key events in the period up to 1994 that directly affected Gülen and the Movement as collective actor. (For reasons that will become clear, the events after 1994 are best treated separately.)

Connecting the rise of movements only to their immediate socio-political context does not adequately explain the full range of collective action – very different kinds of movements can and have emerged from the same background conditions. Also, it is unsatisfactory to study a movement in one context in terms derived from the study of other movements in a different context, because variations in structure, laws, policies, and culture lead to differences in strategy, leadership styles and resource mobilization. With respect to the emergence, dynamics and outcomes of any social movement in Turkey (especially in the case of the kind of multi-purpose civic action that characterizes the Gülen Movement), the political system, its institutions and processes, and the larger social and cultural ethos, constitute highly significant material factors. That is why it is necessary to trace the seeds of collective action in Turkey to the early Republican years, when a new state and society formed. To understand contemporary social phenomena in Turkey, we need to understand the changing circumstances in which the attempt was made to establish, and then hold on to, a nationalist, laicist, and Westernized republic after the end of the Ottoman Empire.

Crises and conflicts; demands for modernization

1. The Republican era: One-party rule

In July 1923, the Turks won sovereignty over eastern Thrace and all of Anatolia. In August, the delegates in the national Parliament fell to infighting over the political course and nature of the future regime. After lengthy disquisitions and eventual intimidation by Mustafa Kemal, Parliament abolished the sultanate and deposed the sultan but retained the caliphate with no political authority. However, many in Parliament did try to invest the caliphate with such authority, aiming thereby to retain influence with other Muslim lands and populations. Then Mustafa Kemal proposed an amendment and, on October 29, 1923, transformed the nation into ‘the Republic of Turkey’. In 1924, at his urging, Parliament abolished the caliphate, the Ministry of Religious Endowments and the office of Shaykhulislam (the highest religious authority) and assigned their responsibilities to two newly established directorates under the government. It abolished the Ministry of the General Staff, and shut down sharia courts and madrasas. The Law on the Unification of Education placed religious secondary education under the Ministry of Education, reorganized the madrasa at the Süleymaniye Mosque (Istanbul) as a new Faculty of Divinity and enforced coeducation at all levels.

These changes put the military and religious cadres under governmental control and the potential for an Islamic state (the most likely challenge to the legitimacy of the Republican regime) was thereby quashed. In addition, Parliament accepted that Turkey was no longer a world power – its frontiers were to be bounded by the Turkish-speaking population of the Republic – and it would not entertain any vision of transnational leadership in any respect. The initial, occasional and individual, reactions to these changes were suppressed by the state apparatus. When, later, 32 parliamentarians, not happy about the changes, broke with the party and formed the Progressive Republican Party, Mustafa Kemal’s People’s Party changed its name to the Republican People’s Party (RPP).

The partition of the state at Sevres, the invasion by the Allied Forces, and the British influence on Kurdish nationalist aspirations, nurtured a peculiar Turkish nationalism and aggravated relations with the Kurds, who previously had for the most part supported the Turkish nationalists. A law passed in 1924 forbidding publications in Kurdish widened the chasm between the Turkish nationalists and the Kurds. When a Kurdish nationalist rebellion in religious garb, led by Sheikh Said, erupted in 1925, the Turkish government issued a law on Maintenance of Order, granting itself extraordinary powers to ban any group or publication deemed a threat to national security. That threat has been used repeatedly ever since by defenders of the system and vested interests. A good example was the establishment in 1925 of the Independence Tribunals (ITs). Enabling the execution of 1,054 people, the ITs played a significant role in suppressing rebellions – the Sheikh Said rebellion, for instance, was ended quite quickly with his arrest and execution.

ITs also snared many others, including Said Nursi, the most important Islamic thinker of the Republican era. Nursi was an Islamic modernist whose writings mapped out an accommodation between the ideas of constitutional democracy and individual liberty and religious faith. During the war years, he had fought against the foreign invasion and for independence, and spoken out against both modern Islamic authoritarianism and economic and political backwardness and separatism. His ideas for a modern Islamic consciousness emphasize the need for a significant role for religious belief in public life, while rejecting obscurantism and embracing scientific and technological development. Although he was not involved in any rebellions, ITs sentenced him, along with many hundreds of others, to exile in western Anatolia.

In 1926, the government declared that it had uncovered a conspiracy to assassinate Mustafa Kemal and, in the next two years turned the ITs on all its enemies. All national newspapers were closed and their staff arrested on grounds of compromising ‘national security’. The Progressive Republican Party was shut down, its leaders accused of collaborating in the conspiracy and arrested for treason. Under public pressure several prominent figures were released but others, though they had once worked closely with Mustafa Kemal, were executed.

2. Laicism

A strongly Kemalist Parliament – for all practical purposes a one-party state – enacted a series of measures between 1925 and 1928 to secularize public life. Mustafa Kemal believed that Turkey must renounce its past and follow the European model of progress. He accordingly set about eliminating all obstacles to a laicized and Westernized nation-state.[1]

Dervish houses were permanently closed, their ceremonies, liturgy and traditional dress outlawed. Kemal publicly denounced the fez and the hijab (veil) as symbols of politicized Islam, as the headgear of a barbarous and backward religiosity, as a foreign innovation. Asserting that Turkish peasant women had traditionally worn only a scarf around their hair, he depicted the hijab as representing subordination of women by a reactionary political ideology. Parliament passed a law requiring men to wear brimmed hats and outlawed the fez. Women were given the right to vote and stand for election. The day after Christmas 1925, Parliament adopted the Gregorian calendar, in place of the Islamic one, as ‘the standard accepted by the advanced nations of the world’, and it changed the Muslim holy day of Friday into a weekday, and instituted Sunday as a rest day.

The following year (1926), Parliament repealed Islamic Law and adopted a new Civil Code, Penal Code and Business Law, based on the Swiss, Italian, and German codes, respectively. In 1928, it deleted from the constitution the phrase ‘the religion of the Turkish state is Islam’. The constitution did not yet state that Turkey was a secular state – that was to come in 1937 – but the intent was clearly to secularize, and to make Westernized forms of social order more visible in, the public sphere.

In 1928, the new alphabet based on the Latin was accepted instead of the Arabic script. It was argued that the new alphabet would help raise literacy. If conceivably true, the low literacy rate could hardly be blamed on a script that had served written Turkish well for about a thousand years. The low levels of literacy were more particularly the result of the prolonged wars, an ineffective system of public education and the belief that having an effective one was an unnecessary luxury during wartime. Rather, reform of the script had historical, cultural, and political intent: use of the Arabic script had identified the Turks as belonging to Islamic civilization and history; use of the Latin characters would identify them with the direction of European civilization and modernity. At a stroke, the new regime totally renounced its past and embraced the revolutionary concept of history. In not learning the Arabic script, the children of the Turkish revolution would also not learn Islamic tradition and, indeed, would be unable to read its greatest literary monuments, or the documents produced only a few years before in the Ottoman Empire.

In the 1920s, the State looked to develop an indigenous, elite entrepreneurial class that would be loyal to and defend the new status quo – a nationalist bourgeoisie. In 1927, it provided to these privileged private citizens transfer of state land, tax exemptions, state subsidies, discounts on transport, and control of state monopolies. During the 1930s these citizens formed the core of the statist-elitist-laicists, whose actions will come up in the arguments in this and later chapters [chapters 3 and 4]. They were also the first of the protectionist vested interests to exploit State-owned Economic Enterprises (SEEs) and other state resources.

The shift to protectionism and statism hardened as the 1930s wore on and deepened the effect of the ensuing economic woes: agricultural prices collapsed causing peasants to fall into severe debt; industrial wages stagnated. The Republican revolution had reached a deadly plateau. Government economic policy drew fierce criticism and occasionally led to violent public reaction. The state centralized economic planning and organized several investment banks as joint stock companies to provide credit to agriculture, develop the mining and power industries, and finance industrial expansion. It also monopolized communications, railroads, and airlines.[2]

3. Cultural revolution

The Republican regime was both deliberate and selective in what it remembered and appropriated of the past. It linked the emerging national identity to Anatolian antiquity. The history and language reforms were part of a sus tained campaign to erase the pre-existing culture and education. Mustafa Kemal personally directed the scientific and literary activity of the later 1920s and 1930s.[3] In 1932, he founded the Turkish History Research Society and charged it with discovering the full antiquity of Turkish history. He theorized that Anatolia had been first settled by Sumerians and Hittites, whom he claimed as Turkic peoples that had migrated from the central Eurasian steppes carrying with them the underlying building blocks of ‘Western civilization’. Also at his command, a Turkish Language Society was established in the same year. The ‘ Sun Language Theory’ was developed, asserting that Turkish was the primordial human tongue from which all others derived. These theories made a deep, enduring impression on the generations that grew up on the textbooks teaching them. Education was designed to make pupils and citizens proud of their Turkish identity and suspicious of the Ottoman past, while also countering Western prejudices about Turks and Turkey. The explicit aim of the Turkish Language Society was ‘to cleanse the Turkish language of the accumulated encrustations from the Arabic and Persian languages’ and from the conceptual categories of the Islamic intellectual tradition. In the following decades the Society’s officials made a concerted effort to introduce substitute or newly coined words. They were largely successful. The current generation of Turkish speakers find works from the early Republican era – including, ironically, the speeches of Mustafa Kemal himself – unintelligible unless translated into contemporary Turkish. Publication in languages other than Turkish was forbidden. In the 1920s, eighty percent of the words in the written language derived from words of Arabic and Persian origin; by the early 1980s the figure was just ten percent. By providing historical roots outside Ottoman history, the Republic’s ideology combined the goals of Westernization and Turkish nationalism, claiming that Western civilization really originated in a Turkic Eurasian past, which the Ottoman Empire had obscured. As political scientist Binnaz Toprak sharply observed, these policies produced ‘a nation of forgetters’.

In 1933, a law reorganized the Darulfunun (literally, ‘home of the arts’, an Ottoman university founded in the fifteenth century) into Istanbul University and purged its faculty in favor of those supportive of Mustafa Kemal’s program for national education. In 1934, the State required all citizens to adopt and register family names. Many potentially useful administrative advantages might well be imagined from a system of alphabetized family names, but the change expressly required that the names be authentically Turkish: names derived from Arabic or Persian roots, or from other ethnic origins (Jewish and Armenian, for example), were not permitted. The measure thus reinforced the national, ethnic identity of the citizens, as distinct from (in particular) their religious identity. The state effectively bound the personal destiny and identity of its citizens to that of the nationstate. In 1936, the government monopolized the authority to broadcast. At the same time, nationalists were advocating the use of Turkish in Islamic liturgy. Parliament established a fund to produce the Turkish version of the Qur’an; Atatürk encouraged the use of Turkish for mosque prayers, Friday sermons and for the call to prayer. After some public resistance (and violent reactions from the state to this resistance), the prayer liturgy remained in Arabic, but the call to prayer began to be done in Turkish, and this was made compulsory in 1941.[4]

The Republican People’s Party (RPP) established ‘ People’s Houses’ and ‘ Village Institutes’. By 1940, more than four thousand People’s Houses had been founded to facilitate the development of popular loyalties and to communicate to citizens their mission and values as formulated by the regime. In 1935, Mustafa Kemal demanded a new strategy for education, which went nation-wide in 1940 through the Village Institutes. The graduates were expected to teach and emphasize techniques of agriculture and home industry, and to inculcate the fundamental ideology of the Republic. These Institutes were widely resented. The people accused the mastermind behind the Institutes of being a communist and the Institutes of being agents of one-party rule and atheistic. They mistrusted the system also on account of its control rather than transformation of their affairs, as it consistently failed to realize land redistribution or relieve them of the power of landlords.

In 1931, Mustafa Kemal had outlined his party (RRP) ideology in six ‘fundamental and unchanging principles’, declaring it to be ‘republican, nationalist, populist, statist, laicist, and revolutionary,’ concepts incorporated into the constitution in 1937 as definitive of the basic principles of the state. While the political system and ‘ideology’ of Turkey remains Kemalism or Atatürkism[5], the last three of the six principles became contentious over time. ‘ Etatism’ or ‘ statism’, meaning the policy of state-directed economic investment adopted by the RPP in the 1930s, was not universally accepted as a basic element of Turkish nationhood and eventually abandoned. ‘ Laicism’ or ‘ secularism’ has been variously interpreted by those at different points on the Turkish political spectrum. It refers in fact to the administrative control of religious affairs and institutions by the state – rather than to separation of ‘state’ and ‘religion’ – and to the removal of official religious expressions from public life, but it also implied in principle freedom, ‘within these bounds’, of religious practice and conscience. ‘ Revolutionism’ – in much later years replaced by the term ‘reformism’ – as one of the least articulated principles, suggests an ongoing openness and commitment to change in the interests of the nation. In reality, as Turkish history since the early days of the Republic has repeatedly shown, some things can hardly be discussed, let alone changed.

Sociologist Emre Kongar considers the Turkish social and cultural transformation as unique – in the totality of its ambition and in its success in replacing, with a synthesis of Western and pre-Islamic Turkish cultures, the previously dominant Islamic culture of an Islamic society. However, the drastic reforms – from grand political structures to the everyday matters of eating, dressing and celebrations – pushed through in such a short period of time, would need a longer period for assimilation. They were not all welcomed but, to the contrary, provoked hostile reactions, which has had the effect of enduringly politicizing certain issues in Turkey.

4. İnönü, ‘the National Chief’ and ‘Eternal Leader’

After the death of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1938, his reforms were consolidated by his successor, İsmet İnönü. Parliament granted İnönü the titles of ‘the National Chief’ and ‘the Eternal Leader’, with enhanced powers in anticipation of possible challenges to the regime, powers much greater than those of the last two Ottoman sultans. The Second World War began a year later. İnönü’s forceful use of the crisis ensured, through imposition of martial law in much of the country, the maintenance of the Kemalist structure, and it kept Turkey out of the war.

During the war years there were shortages of basic goods and cash, as well as inflation. The government imposed an extraordinary ‘ capital-wealth tax’ on property owners, farmers, and businessmen in 1942. The tax schedules were not prepared with formal income data but left to the personal estimates of local bureaucrats, who divided taxpayers according to profits, capacity, and religion – Muslim, non-Muslim, Foreigner, and Sabbataist (Jewish converts). Many were financially ruined by this tax, against which no appeals were admitted. Resisters were, after arrest, deported or sentenced to hard labor. The Turkish financial world was severely shaken.[6] In 1944, İnönü suppressed student protest movements against his policies. Prominent figures were arrested and charged with ‘plotting to overthrow the government’ and to bring Turkey into the war on Germany’s side.[7]

Turkey was still underdeveloped: there were shortages of tractors and paved roads; a mere handful of villages had electricity; barely a fraction of the country’s agricultural potential had been realized. Villagers resented the increased state control, the increased taxation, and the symbols of state-imposed secularization. Wartime price controls destroyed their profits. In addition, while already poor and over-taxed, villagers were forced to build schools, roads, and facilities for masters who often turned out to be aloof mouthpieces of the hated regime. The military police violently suppressed dissent. In the towns, the appalling economic conditions, censorship of the press, and restrictions on personal freedom, fed a growing exasperation. Even after signing the UN Charter, Turkey prolonged martial law for more than a year, press censorship remained heavy, and no labor union activity was tolerated. Anti-government sentiment grew accordingly: state civil servants who had suffered heavily from inflation, and businessmen, both Muslim and Christian, who had carried the burden of the capital tax, united in opposition to the single-party authoritarianism.[8]

Four parliamentarians, Celal Bayar, Refik Koraltan, Fuad Köprülü, and Adnan Menderes, formally requested that the constitutional guarantees of democracy be implemented. Köprülü and Menderes published articles in the press critical of the RPP. They and Koraltan were expelled from the party; Bayar resigned his membership. Following domestic and external pressures, İnönü in 1946 allowed the four dissidents to form the Democrat Party (DP). The DP served as an umbrella under which all who mistrusted or opposed the RPP government sought refuge and voiced the resentments that had been building up over previous years.[9] Then, before the DP was able to organize fully, the RPP called early elections in May 1946, which it won.

However, the victorious RPP all but split in a tussle between its single- party statist and its reform-minded members. The RPP leader was forced to resign, and the party adopted a new development plan. Turkey joined the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and then implemented some economic and political corrective measures. The hated founder and head of the Village Institutes was relieved of his duties. The Education Department decided that religion could be taught in schools, and a Faculty of Divinity opened in Ankara in 1949. Under international pressure since signing the UN Charter, the RPP also relaxed its attitude toward popular Islam. Even so, in the 1950 elections, it won only 69 seats as against the DP’s absolute majority of 408.[10]

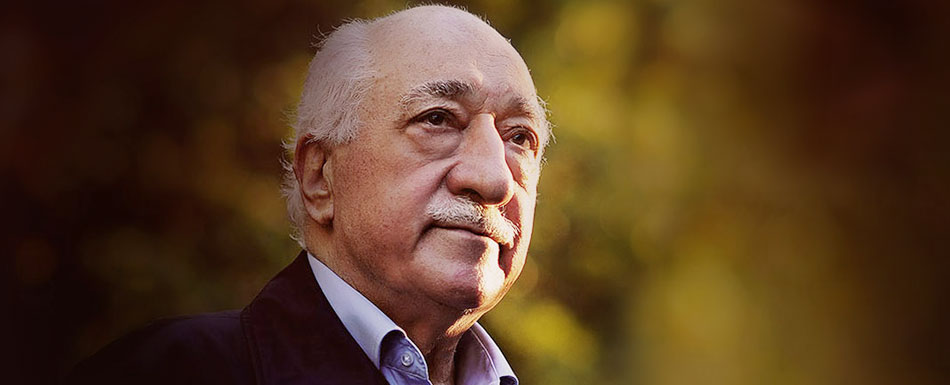

It is during this period, in 1941, that Fethullah Gülen was born, in a village in Erzurum, eastern Anatolia. His parents took charge of his early education and religious instruction. There were few opportunities for a general secular education for ordinary Turkish people at this time. Fethullah Gülen’s parents sent him to the nearest state primary school for three years. However, because his father was assigned by the state to a post as preacher and imam in another town, one that had no secondary school, Fethullah Gülen was unable to progress to secondary education. Although at this time mosques and congregational prayer were allowed, all other forms of religious instruction and practice were not. Even so, Fethullah Gülen’s parents, like many other ordinary Turkish people, kept up the Turkish Islamic tradition and made sure that their children learned the Qur’an and basic religious practices, including prayer. They avoided confrontation with the authorities and the regime, concealing the fact that they were providing elementary Islamic instruction to their own and their neighbors’ children.[11]

5. Democrats, 1950–1960

In 1950 power passed from a single-party dictatorship to an elected democratic government. But then something happened that would recur in different guises to haunt Turkey right up to the present: top army officers offered to stage a coup d’état to suppress the elected government and restore İnönü to power. For fear of an international intervention, İnönü declined. The Democrat victory was received with jubilation; Bayar became the President, Menderes the Prime Minister.[12]

From 1948 to 1953, production, especially in the agricultural sector, GDP and economic growth, all boomed. More than 30,000 tractors were imported, which farmers could finance through credits; dams were built; cultivated land increased by more than fifty percent and total yields swelled; major cities were linked to a national highway system for the first time; the miles of paved highways quadrupled and improved feeder roads made it easier for thousands of newly imported trucks to get farm produce and goods to market. In these years the DP presided over a period of lower cost of living, increasing production and employment, tax reform, customs reforms, and support of private capital and foreign investment.[13]

Then, from 1954, overall economic growth slowed. The expansion had been financed with borrowed money and fuelled by splendid harvests. With low levels of hard currency, the country was left with large trade and balance of payments deficits. In 1955, import restrictions returned and foreign investors refused requests for new loans. The privatization program never got off the ground. The largest firms were still the SEEs. The government’s building of cement plants, dams, and highways all at the same time was simply trying to do too much. In September, the attempt of Greek Cypriots to unite with Greece caused riots in Istanbul and Izmir. When thugs attacked Greek merchants, martial law was declared. Some of the media began to act the role of an opposition party. The government threatened to prosecute the publication of news that could ‘curtail the supply of consumer goods or raise prices or cause loss of respect and confidence in the authorities’. Two daily newspapers were closed for doing just that.

The largest industrial conglomerates in today’s Turkey had their origins in this period. Mechanization of agriculture forced surplus laborers to migrate to the cities in search of work. Urban traders and businessmen accumulated enormous wealth and clamored for political leverage proportionate to their economic standing. The Confederated Trade Unions of Turkey also expressed the desire for greater political participation. As the DP identified with free enterprise and free expression of religious sentiment, it attracted many of the successful entrepreneurs and the conservative peasants. However, the rapid economic growth had had social consequences, in particular rousing political envy among those who felt threatened, that, in its enthusiasm for the boom, the government had failed to foresee.[14] The later years of the period were characterized by thugs, students and security forces fighting on the streets, with media galvanizing discontent on certain issues in favour of vested interests – recurrent motifs in the country’s modern history.

Particularly ominous was the growing resentment of the established ‘Republican’ bureaucratic, military, and intellectual elites, whose laicist and statist assumptions about national life were being challenged by democratically oriented policies. The ostensible reason for the military officers’ resentment was that their salaries did not keep up with inflation. In 1950 the DP government, wanting to purge the revolutionary core in the army general staff, discharged the top brass with ties to İnönü. Then in 1953, uncertain of the goodwill and potential neutrality of the university faculties, it prohibited university faculties from political activity by law. A 1954 law introduced an age limit which forced faculty members and some judiciary to retire – these were the Republican cadre, then over sixty, who had been in post for twenty-five years.

Democrats looked to thread a way between the pressures from constitutional secularism and their electoral base. In 1950, they ended the twenty- seven-year ban on religious broadcasting with twenty minutes per week of Qur’anic recitations on radio, and introduced religious teaching into the public school curriculum. More Imam-Hatip schools were opened and the call to prayer (adhan) was once again made in Arabic. The unloved People’s Houses and Village Institutes were closed.[15] Defaming Atatürk was made a criminal offence after a few busts of him were smashed. The courts found the recently organized Nation Party guilty of using religion for political purposes and dissolved it.

In spite of the DP’s concessions to the secularists and statists, conditions became strained. The defenders of the status quo in Turkey (who will come up again in the later parts of this narrative) counter-mobilized against the elected government and civil society. Citing the economic downturn, displeased businessmen and academics withdrew their support for the DP. A dean at Ankara University delivered a ‘political lecture’ and was dismissed; students were mobilized for protests; some academics resigned. From 1955 onwards, officers in the armed forces began noticeably to conspire against the government.[16]

Discontent in the military stemmed from complicated social roots. Since the end of World War II, the prestige of a military career in Turkey had slowly declined. Democratization had marginalized those accustomed to playing a central role in the country’s affairs. A small number of officers within the army formed a kind of oppositional, reactionary movement against the elected government, incorporating revolutionary ideology into the training of cadets and junior officers. Menderes, wary of the influence of the officers and İnönü, made a military reformer his minister of defense, but opponents among the military top ranks managed to have him dismissed. After that, Menderes ingratiated himself with the generals, but he was ill-informed about the junior officers frustrated by the hierarchy of the officer corps and hungry for economic and political power. After Turkey joined NATO in 1952, those officers started to receive advanced training in Europe and the US, and to interact with the American and NATO officials based in Turkey after 1955. They complained about ‘purchasing power’ and ‘standards of living’ in Turkey. In the 1957 elections, the DP, despite taking almost 48 percent of the vote, lost its majority. The RPP meanwhile found new support among intellectuals and businessmen defecting from the DP. Two months later, nine junior army officers were arrested for plotting a coup.[17]

Through 1958–59, the DP government implemented some economic measures, rescheduled its debt, and received further loans from the US, OEEC (Organization for European Economic Co-operation), and IMF. In 1959, it applied for membership in the European Economic Community (EEC). A partial recovery began. However, discontent among state servants and the elite persisted. The RPP went on the offensive. İnönü’s tour of Anatolia became the occasion for outbreaks of violence along his route. Menderes ordered troops to interrupt the tour by İnönü in 1960, but İnönü called their bluff and embarrassed the troops into backing down. Student protests and riots started in April. On one occasion, police opened fire, killed five and injured some more. Under their top officers’ direction, cadets from the military academy staged a protest march against the government but in solidarity with the oppositional student movement. Some elements of the armed forces openly displayed their opposition to the elected civilian authorities. Martial law was declared. On May 14, crowds demonstrated in the streets. On May 25, Parliamentarians fought within Parliament leaving fifteen injured. On May 27, the armed forces took over the state.[18]

During this decade (1950–60) Fethullah Gülen completed his religious education and training under various prominent scholars and Sufi masters leading to the traditional Islamic ijaza (license to teach). This education was provided almost entirely within an informal system, tacitly ignored and unsupported by the state and running parallel to its education system. At the same time, Fethullah Gülen pursued and completed his secondary level secular education through external exams. In the late fifties, he came across compilations of the scholarly work Risale-i Nur (Epistles of Light) by Said Nursi but never met its famous author. In 1958–9, he sat for and passed the state exam to become an imam and preacher. On the basis of the exam result he was assigned by the state to the very prestigious posting in Edirne.[19]

Throughout this service he maintained his personal life style of devout asceticism while mixing with people and remaining on good terms with the civic and military authorities he encountered in the course of that service. He witnessed how the youth were being attracted into extremist, radical ideologies, and strove through his preaching to draw them away from that. Using his own money he would buy and distribute published materials to counter an aggressively militant atheism and communism. He saw the erosion of traditional moral values among the youth and the educated sector of Turkish society feeding into criminality and political and societal conflict. These experiences were formative influences on his intellectual and community leadership and reinforced his faith in the meaning and value of human beings and life.[20]

6. Military coup d’état

Some circles in Ankara and Istanbul welcomed the military coup; much of the general public accepted it with sullen resignation. Declarations of nonpartisan objectives notwithstanding, the military’s actions confirmed the general perception that the coup was an intervention against the DP government on behalf of the RPP. The DP was denounced as an instrument of ‘class interests’ aligned with ‘forces opposed to the secularist principles of Atatürk’s revolution’. DP Parliamentarians were arrested and the party closed down.[21]

Calling itself the National Unity Committee (NUC), a junta of 38 junior officers exercised sovereignty and declared a commitment to the writing of a new constitution under which Parliament would resume its role. General Cemal Gürsel, nominal leader and chairman of the NUC, became President, Prime Minister, and Commander-in-Chief. The NUC grouped into three factions, which from the outset disagreed about aims and principles. One faction comprised old school generals (pashas) who wanted to restore civil order and civilian rule. The second faction, more interested in social and economic development, wanted a planned economy led by SEEs and to hand power to İnönü and the RPP. The third faction, made up of younger officers and communitarian radicals, advocated indefinite military rule in order to effect fundamental political and social change from above, a sort of non-party nationalist populism on the pattern of Nasser’s Egypt.[22]

The power struggle among these factions continued until the pashas dissolved the NUC and formed a new NUC, exiling fourteen radical junior officers to Turkish embassies abroad. The pashas only later realized how far the radicals had disseminated revolutionary views among the junior officer corps. They purged some of those, but sub-groups reformed, conspiring to seize control and overhaul the whole political and social system. Aware of the continued danger and wanting to prevent their ‘economic marginalization’, senior officers formed OYAK and the AFU. OYAK was a pension fund for retired officers financed by obligatory salary contributions; it developed very quickly into a powerful conglomerate with vast holdings.[23] AFU (Armed Forces Union) was set up to provide a forum for discussing issues of concern under the supervision of the top ranks: the pashas intended to gain control over the junior officers and to ensure there would never be another military rebellion that they themselves did not lead and direct.

Meanwhile, those who favored a return to a single-party system deadlocked the Constitutional Commission. After a purge, the Commission eventually produced a document. However, a rival group of professors submitted another draft and convinced the NUC to appoint an assembly made up of the NUC and ‘some’ politicians. The compromise constitution, written by two professors, passed in a deeply divided referendum in 1961.[24]

The constitution brought significant structural changes to society and government. It established a bicameral legislature. The upper chamber Senate was directly elected for six-year terms, but members of the NUC and former presidents of Turkey became lifetime senators and fifteen others were appointed by the president. The lower chamber was popularly elected by proportional representation. Legislation had to pass both chambers. The national budget was reviewed by a joint commission of the two chambers. A Constitutional Court (CC) was established, fifteen members of which were drawn from the judiciary, parliament, law faculties, and presidential appointments. The CC reviewed laws and orders of Parliament at the request of individuals or political parties. The president of Turkey would be elected by Parliament, from among its own members, for a single term of seven years. His office maintained a certain independence from the legislature. The constitution guaranteed freedom of thought, expression, and association, which the 1924 constitution had not included. Freedom of the press was limited only by the need to ‘safeguard national security’. The state had the power to plan economic and cultural development advised by the State Planning Organization. The National Security Council (NSC) was institutionalized by law, chaired by the President and made up of the chief of the general staff, heads of the service branches, the prime minister, and ministers of relevant cabinet ministries. The NSC would advise government on matters of domestic and foreign security. Through its general secretariat and various departments, the NSC was gradually to develop into a decisive political force, as ever greater portions of political, social, and economic life came under the rubric of ‘matters of national security’.[25]

The coup was a grave error, set a bad example to the rest of the military cadre about ignoring the military hierarchy, and also aroused their ambitions for the successive military interventions in Turkish domestic politics, especially in 1971 and in 1980, which halted the democratization process so that Turkey lost valuable time in its economic as well as democratic modernization.[26]

7. After the executions: 1961–1970

Hundreds of DP deputies were tried on charges of corruption and high treason. The trials and executions of DP leaders during the national elections of 1961 made obvious the junta’s true political ambitions. Partly in response to public appeals for clemency, the sentences of eleven of the fifteen condemned to death were commuted to life imprisonment. The former president was spared on account of his advanced age and ill health. Prime Minister Adnan Menderes and the Foreign Minister Fatin Rüstü Zorlu, and Finance Minister Hasan Polatkan were hanged in September.[27]

In the general elections held a month later, İnönü’s RPP won 73 seats. The core of the DP reformed as the Justice Party (JP) was only three seats short of a majority in the lower chamber. Cemal Gürsel, the coup leader, became President. The election results50 could well be interpreted as a repudiation of the new regime and its constitution. Political instability marked the next several years, as a series of short-lived coalition governments headed by İnönü, with the support of the army, tried to implement the constitution. In late 1961, workers began demonstrating in the streets demanding their right to strike. Junior officers, determined to prevent a new Democrat take-over, plotted a coup in February 1962 under Colonel Talat Aydemir. Aydemir, a key conspirator in the 1950s, had been unable to participate in the coup due to his posting in Korea. This time he took part and was arrested. Circumstances forced the JP and RPP into a brief coalition until May. When it collapsed, İnönü formed another coalition that, thanks to concessions, managed to last more than a year. Meanwhile, a second coup attempt by Colonel Aydemir was thwarted, and he was executed in May 1963. Local elections in 1963 made it clear that the governed no longer gave consent to the RPP. İnönü resigned. The winning JP, however, failed to form a new government. Once again, İnönü managed a coalition with the independents, which survived for fourteen months, thanks largely to the Cyprus crisis preoccupying everyone throughout 1964. In February 1965, the budget vote brought down the government, and the country limped to elections in October.[28]

Social and economic goals of public policy were never achieved because vocal opponents to development planning were in the cabinet after the first coalition. For instance, the cabinet rejected proposed reforms for land, agriculture, tax, and SEEs. The State Planning Organization advisors were forced to resign. The government’s lack of political commitment to its work, the increasing politicization of appointments and its partisan protection of vested interests, instead of those of the whole nation, weakened state institutions.

In 1965, Süleyman Demirel’s JP won the elections with an outright majority. Demirel assured the generals that he would follow a program independent of the old Democrats. He reconciled with the military, granting them complete autonomy in military affairs and the defense budget. However, the irregular economic growth of the 1960s gradually alienated his lower middle class constituency. The JP began to fragment, some following Colonel Alparslan Türkeş into nationalism, others following Necmettin Erbakan into religious pietism. Türkeş, a key figure of the 1960 junta, had returned from exile abroad in 1963, retired and later took over the chairmanship of the Republican Peasants’ National Party (RPNP). Under his direction the RPNP adopted a radically nationalist tone. Erbakan formed the National Order Party (NOP) in 1970, the first of a series of political Islamist parties in Turkey. He gained a reputation as a maverick for freely airing intemperate remarks and advocating a role for Islam in public and political life.

In the 1960s, the RPP argued with the same old rhetoric that Demirel’s policies had forsaken the principles of Atatürk and would ruin the peasant and worker. Bülent Ecevit, who had been the Minister of Labor in the three RPP-led coalitions till 1965, asked the RPP to shed its elitist image and trust the common people to know what was best for them. Some deputies did not like his suggestions and left the party. However, Ecevit had understood that the voters had supported Menderes and later Demirel because they felt alienated by the RPP’s arrogance and because the other parties’ programs were better.[29]

By 1970, Turkey faced a mounting crisis whose origins lay generally in deteriorating economic conditions, the massive social changes since the 1950s, a loss of confidence in the State, and the circumstances of the Cold War. On the other hand, there were some successes in Turkish-foreign joint ventures: an oil-pipeline, a dam, two irrigation projects, and associate membership of the EEC. By the end of the decade, the state monopolies, the publicly owned banks, and the recently founded OYAK had become fairly successful and sizeable enterprises. Mechanization pushed labor to western Europe: the migrants’ cash remittances from Europe were Turkey’s most important source of foreign exchange.

In 1967 leftists formed the Confederation of Revolutionary Workers’ Unions (DISK). Its president was Kemal Türkler, a founding member of the (communist) Turkish Workers’ Party (TWP). DISK was anti-capitalist and politically radical activist, encouraging street demonstrations and strikes to achieve its objectives. Proportional representation brought such small parties into Parliament, with the result that public life became increasingly influenced by the activities of small extremist groups of the left and right. Throughout the late 1960s and 1970s, they exerted an influence on politics beyond their numbers. The milieu in universities enabled leftists to form on-campus ‘idea clubs’ with agendas anticipating the imminent radical transformation of society. Spreading outward from the universities, politicization and polarization increasingly infected public life. National dailies, language, music, art, and festivals came to be known as leftist or rightist; people could be identified on the political spectrum by the vocabulary they used in everyday speech.

One of the most notorious extremist groups that emerged in this period was Revolutionary Youth (Dev-Genç). It grew out of an effort to link the ‘idea clubs’ at universities nationally under Marxist leadership. It advocated the violent overthrow of the state. The left in general stressed opposition to imperialism, to the West, and to American bases. Americans and their interests represented, to the leftists, subservience to international capitalism and militarism in Turkey. The correspondence in 1964 between American President Johnson and then Prime Minister İnönü, published in 1966, in which Johnson threatened not to back Turkey in the event of a Soviet attack, turned public opinion dramatically against the US. For leftists, the letter confirmed that the US had no real interest in Turkey beyond a cold calculation of its place in the international power balance. They accused Demirel and the JP of being ‘American stooges’. Demirel announced a government and police crackdown on ‘communists.’

The leftists were also targeted by the right, which, in general, coalesced around a common anti-communism, in many (but not all) cases, advocating conservative Islamic piety and values as normative for Turkish society. A large portion of the Turkish populace was indeed socially and religiously conservative – a fact not lost on Demirel, who was not above occasionally manipulating traditional Islamic social values or fears of the Soviets for political purposes. More virulent forms of nationalism and anti-communism became evident in the late 1960s. There was sporadic anti-American violence: in 1966, rioters attacked the US consulate, the office of the US Information Agency and the Red Cross; increasingly violent demonstrations accompanied the visit of the US Sixth Fleet; the US Information Agency in Ankara was bombed. Leftist and rightist groups both took part in demonstrations that turned increasingly violent in late 1967.

In 1968, leftist students seized the buildings at Ankara University demanding abolition of the examination system and fee structure. In May 1969, a rector and eleven deans protested against the government and resigned. In August, demonstrators belonging to the leftist unions occupied the Eregli Iron-Steel plant. Riot police were unable to evict them. Airport employees went on strike in September. Fighting took place all over the country during the elections in October. The JP maintained a shaky Parliamentary majority. The RPP was still in its identity crisis. Six other parties entered Parliament, though none won even seven percent of the popular vote. Then, in 1970, because of economic problems, unpopular corrective measures and a threemonth- late budget, JP dissidents forced Demirel to resign.[30]

In 1961, Fethullah Gülen began his compulsory military service in Ankara. By chance he was in the military unit commanded by Talat Aydemir. However, not being a professional soldier, Fethullah Gülen had no contact with Aydemir himself or with the military cadets and high-ranking officers who took part in the conspiracy. On the day of the coup, he and his fellow troopers were confined to barracks and thus only witnessed the coup and its aftermath through radio announcements and briefings from officers. After the coup, Fethullah Gülen was sent to Iskenderun, where he would do the second posting that completes compulsory military service. Here, his commanding officer assigned to him the duty of lecturing soldiers on faith and morality, and, recognizing Fethullah Gülen’s intellectual ability, gave him many Western classics to read. Throughout his military service Fethullah Gülen maintained his ascetic lifestyle as before.[31]

In 1963, following military service, Fethullah Gülen gave a series of lectures in Erzurum on Rumi. He also co-founded an anti-communist association there, in which he gave evening talks on moral issues.

In 1964, he was assigned a new post in Edirne, where he became very influential among the educated youth and ordinary people. The militantly laicist authorities were displeased by his having such influence and wanted him dismissed. Before they could do so, Fethullah Gülen obliged them by having himself assigned to another city, Kırklareli, in 1965. There, after working hours, he organized evening lectures and talks. In this phase of his career, just as before, he took no active part in party politics and taught only about moral values in personal and collective affairs.

In 1966, Yaşar Tunagür, who had known Fethullah Gülen from earlier in his career, became deputy head of the country’s Presidency of Religious Affairs and, on assuming his position in Ankara, he assigned Fethullah Gülen to the post that he himself had just vacated in Izmir. On March 11, Fethullah Gülen was transferred to the Izmir region, where he held managerial responsibility for a mosque, a student study and boarding-hall, and for preaching in the Aegean region. He continued to live ascetically. For almost five years he lived in a small hut near the Kestanepazarı Hall and took no wages for his services. It was during these years that Fethullah Gülen’s ideas on education and service to the community began to take definite form and mature. From 1969 he set up meetings in coffee-houses, lecturing all around the provinces and in the villages of the region. He also organized summer camps for middle and high school students.

In 1970, as a result of the March 12 coup, a number of prominent Muslims in the region, who had supported Kestanepazarı Hall and associated activities for the region’s youth, were arrested. On May 1, Fethullah Gülen too was arrested and held for six months without charge until his release on November 9. Later, all the others arrested were also released, also without charge. When asked to explain these arrests, the authorities said that they had arrested so many leftists that they felt they needed to arrest some prominent Muslims in order to avoid being accused of unfairness. Interestingly, they released Gülen on the condition that he gave no more public lectures.

In 1971, Fethullah Gülen left his post and Kestanepazarı Hall but retained his status as a state-authorized preacher. He began setting up more student study and boarding-halls in the Aegean region: the funding for these came from local people. It is at this point that a particular group of about one hundred people began to be visible as a service group, that is, a group gathered around Fethullah Gülen’s understanding of service to the community and positive action.

8. Military coup II

Civil unrest and radicalization continued to grow in the 1970s. DISK organized a general strike in the spring. In August, ominous news of a shake-up leaked from the General Staff. In December, students clashed at Ankara University. The Labor Party headquarters and Demirel’s car were bombed. In February 1971, more than 200 extreme-leftist students were arrested after a five-hour gun battle with the military police at Hacettepe University in Ankara. On March 4, leftist students kidnapped four American soldiers and held them for ransom. A battle ensued when police searched for the soldiers at a dormitory in Ankara University; two students died before the Americans were released. On 12 March 1971, the military seized control of the state, citing the crisis in Parliament, the incompetence of the government, and street and campus clashes between communists and ultra-nationalists, and between leftist trade unionists and the security forces.[32] This was a sad repetition of their previous seizure of power (in 1961) and the same themes recurred in their discourse to justify their action.

The generals said they had acted to prevent another coup by junior officers rather than because they had a specific program to lead the country out of its difficulties. Publicly blaming the political parties for the crisis, they selected a government that would implement the 1961 constitutional reforms. Under martial law, the military arrested thousands – party and union leaders, academics and writers; also they closed down Erbakan’s party, as well as several mainstream newspapers and journals. The National Intelligence Organization used severe repression, including torture, to extract confessions from suspects. The cabinet made no progress and was forced to resign. Constitutional amendments scaled back civil liberties, freedom of the press, and the autonomy of the Constitutional Court. Universities and the broadcast media lost their autonomy to supervisory committees. The National Security Council ‘advice’ to Parliament became binding. A system of State Security Courts (SSCs) was introduced that, in the following years, would try hundreds of cases under the rubric of national security.[33]

B ülent E cevit succeeded İ smet İnönü as the RPP chair. E rbakan put together a new party with much the same leadership and called it the National Salvation Party (NSP). Elections were held in 1973. Though they had very little in common, the RPP and NSP formed a coalition, the first of several that would govern Turkey with diminishing levels of success till 1980.

In Cyprus in July 1974, Greek Cypriot guerrillas, fighting for union with Greece, overthrew the Cypriot President in a coup and replaced him with a guerrilla leader. Killings began. Turkish troops landed in northern Cyprus to protect the Turkish-Cypriots and secured one-third of the island. There the Turkish-Cypriots organized what later, in 1983, became the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). Turkey paid a high price for this move: the substantial cost of assistance to TRNC; a 50 percent increase in its defense budget; diplomatic isolation and damage to its standing in the EC. Further, the US cut off assistance and imposed an embargo, which contributed to Turkey’s grave economic position in the late 1970s. In 1976, Turkey signed a new four-year defense agreement with the US, but the US Congress did not approve it due to Greek and Armenian lobbying.

Between 1972 and 1975, Fethullah Gülen held posts as a preacher in several cities in the Aegean and Marmara regions, where he continued to preach and to teach the ideas about education and the service ethic he had developed. He continued setting up hostels for high school and university students. At this time educational opportunities were still scarce for ordinary Anatolian people, and most student accommodation in the major cities, controlled or infiltrated by extreme leftists and rightists, seethed in a hyper-politicized atmosphere. Parents in provincial towns whose children had passed entrance examinations for universities or city high schools were caught in a dilemma – to surrender their children’s care to the ideologues or to deny them further education and keep them at home.

The hostels set up by Fethullah Gülen and his companions offered parents the chance to send their children to the big cities to continue their secular education, while protecting them from the hyper-politicized environment. To support these educational efforts, people who shared Fethullah Gülen’s service-ethic now set up a system of bursaries for students. The funding for the hostels and bursaries came entirely from local communities among whom Gülen’s service-ethic idea (hizmet) was spreading steadily.

With Fethullah Gülen’s encouragement, around his discourse of positive action and responsibility, ordinary people were starting to mobilize to counteract the effects of violent ideologies and of the ensuing social and political disorder on their own children and on youth in general. Students in the hostels also began to play a part in spreading the discourse of service and positive action. Periodically, they returned to their home towns and visited surrounding towns and villages, and, talking of their experiences and the ideas they had encountered, consciously diffused the hizmet idea in the region. Also, from 1966 onward, Fethullah Gülen’s talks and lectures had been recorded on audio cassettes and distributed throughout Turkey by third parties. Thus, through already existing networks of primary relations, this new type of community action, the students’ activities, and the new technology of communication, the hizmet discourse was becoming known nation-wide.

In 1974, the first university preparatory courses were established in Manisa, where Fethullah Gülen was posted at the time. Until then, it was largely the children of very wealthy and privileged families who had access to university education. The new courses in Manisa offered the hope that in future there might be better opportunities for children from ordinary Anatolian families. The idea took hold that, if properly supported, the children of ordinary families could take up and succeed in higher education.

As word spread of these achievements, Fethullah Gülen was invited, the following year, to speak at a series of lectures all over Turkey. The service idea became widely recognized and firmly rooted in various cities and regions of the country. From this time on, the country-wide mobilization of people drawn to support education and non-political altruistic services can be called a movement – the Gülen Movement.

9. Collapse of public order

Ecevit resigned in 1974 in order to call elections that he thought, after the Cyprus action, his RPP could win. However, leaders of the other parties did not allow an election to be called. Ecevit’s move brought governmental impasse until late 1980. A series of unstable coalitions followed, none of which possessed the strength to manage the economic problems, or control the political violence.[34]

Some enterprises that had taken advantage of foreign capital during the 1950s had grown tremendously in the 1960s. To maintain their position and leading role, and to lobby the government for support, in 1971, owners of the 114 largest firms formed the Association of Turkish Industrialists (TUSIAD). However, the quadrupling of oil prices in 1973 raised the cost of the imports Turkey depended on and consumed about two-thirds of Turkey’s foreign currency income. Inflation and unemployment climbed steadily after 1977. By 1978–79, there were even shortages of basic commodities.

After the 1971 coup, the crackdown on radical leftists by the security forces started a spiral of attacks and retaliations to which there seemed to be no resolution. With Alparslan Türkeş’s appointment as a minister of state from 1974 to 1977, the violent campaign of radical groups against all who disagreed with them escalated and contributed substantially to the collapse of public order by 1980. A 1977 May Day celebration by the leftist unions turned into a battle among themselves and with the police, leaving 39 dead and more than 200 wounded. Leftists retaliated with a wave of bombings, killing several people at the airport and railway stations. A state of virtual war prevailed between DISK, the Turkish Workers’ Party and other leftist groups on the one hand, and the Istanbul police force on the other. Clashes between rightist groups and leftists killed 112 and wounded thousands in Sivas and Kahramanmaras. Ecevit declared martial law.

Violence was at a peak on university campuses. In 1974–75, students disrupted classes, rioted and killed one another, forced the temporary closure of universities, waged battles, and carried out killings and bombings at offcampus venues frequented by students. Academics were beaten and murdered. At Ankara University in 1978, a leftist student, Abdullah Öcalan, formed the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) and began a separatist war in the south-eastern provinces. Americans and NATO personnel were targeted and murdered by the leftists. Although banned, May Day demonstrations organized by leftist labor continued. Clashes between rightists and leftists increased. Members of the security forces, journalists, party officials, labor union leaders, and ministers were murdered; strikes went on for weeks and months.

The divided government, meanwhile, did not take up an austerity plan suggested by Demirel’s economic advisor Turgut Özal. In February, Fahri Korutürk’s presidential term expired: for six months Parliament was unable to elect a successor. The economy was in tatters, with inflation running at 130 percent and unemployment 20 percent. Murderous confrontations between the radicals had taken 5,241 lives in two years. Erbakan’s fundamentalist meetings in Konya stirred up the military. And again, for the third time in twenty years, on September 12, 1980, the military seized direct control of the state. Their discourse framed their action in exactly the same way as in the two previous coups.[35]

The constitution after the 1961 coup had restructured Turkish government and institutions in such a way that it caused the political system to fail. Personal and political liberties were not implemented, nor reforms to land, tax and the SEEs. The system crashed in insurmountable difficulties. Due to inability, or unwillingness, to revise the prevailing political culture for the needs of an open society, together with the consequences of economic crisis, deep fissures opened in society between those who had benefited from the rapid and haphazard social and economic development since 1945 and those who found themselves victims of the inflation, unemployment, and urban migration it engendered. There were those who had benefited from multiparty democracy through their links of patronage with powerful officials, and those who still lived with the residue of the one-party era with its authoritarian model of leadership, the equation of dissent with disloyalty, and party control of state offices. Turkey’s standing in the Cold War contributed to the polarization of society and was also exploited to mask the sources of its problems, and made it impossible to achieve the political consensus necessary to adopt reforms. A major source of the political and social degeneration of the 1960s and the chaos and anarchy of the 1970s was the radical tendencies of students, militants, academics, unions, and officers of the state security apparatuses. Finally, the armed forces, which Parliament had failed to subordinate to civilian rule, put an end to that rule, which the armed forces had themselves established a mere ten years earlier.[36]

In 1976, the Religious Directorate posted Fethullah Gülen to Bornova, Izmir, the site of one of Turkey’s major universities with a correspondingly large student population and a great deal of the militant activism typical of universities in the 1970s.

It came to his attention that leftist groups were running protection rackets to extort money from small businessmen and shopkeepers in the city and deliberately disrupting the business and social life of the community. The racketeers had already murdered a number of their victims. In his sermons, Fethullah Gülen spoke out and urged those being threatened by the rackets neither to yield to threats and violence, nor to react with violence and exacerbate the situation. He urged them, instead, to report the crimes to the police and have the racketeers dealt with through the proper channels. This message led to threats being made against his life.

At the same time, he challenged the students of left and right to come to the mosque and discuss their ideas with him and offered to answer any questions, whether secular or religious, which they put to him. A great many students took up this offer. So, in addition to his daily duties giving traditional religious instruction and preaching, Fethullah Gülen devoted every Sunday evening to these discussion sessions.

In 1977, he traveled in northern Europe, visiting and preaching among Turkish communities to raise their consciousness about values and education and to encourage them in the same hizmet ethic of positive action and altruistic service. He encouraged them both to preserve their cultural and religious values and to integrate into their host societies.

Now thirty-six, Fethullah Gülen had become one of the three most widely recognized and influential preachers in Turkey. For example, on one occasion in 1977 when the prime minister, other ministers and state dignitaries came to a Friday prayer in the Blue Mosque in Istanbul, a politically sensitive occasion in Turkey, Fethullah Gülen was invited to preach to them and the rest of the congregation.

Fethullah Gülen encouraged participants in the Movement to go into publishing. Some of his articles and lectures were published as anthologies and a group of teachers inspired by his ideas established the Teachers’ Foundation to support education and students.

In 1979, this Foundation started to publish its own monthly journal, Sızıntı, which became the highest selling monthly in Turkey. In terms of genre, it was a pioneering venture, being a magazine of sciences, humanities, faith, and literature. Its publishing mission was to show that science and religion were not incompatible and that knowledge of both was necessary to be successful in this life. Each month since the journal was founded, Fethullah Gülen has written for it an editorial and a section about the spiritual or inner aspects of Islam, that is, Sufism, and the meaning of faith in modern life.

In February 1980, a series of Fethullah Gülen’s lectures, attended by thousands of people, in which he preached against violence, anarchy and terror, were made available on audio cassette.

10. Military coup III

In September 1980, the military arrested and placed the prime minister, party leaders and 100 parliamentarians in custody. It dissolved Parliament, suspended the constitution, banned all political activity, dissolved and permanently outlawed all political parties, forbade their leaders to speak about politics – past, present or future – and seized, and subsequently caused to disappear, the archives of the parties of the past thirty years. Martial law was extended to all Turkey. Several thousand were arrested in the first week. The junta wanted in this way to signal its determination to institute a new political order.[37]

The coup leaders, the five commanders of the armed forces, formed the National Security Council (NSC) and gave themselves indefinite and unlimited power. General Kenan Evren became head of state and appointed a cabinet composed mostly of retired officers and state bureaucrats. Martial law commanders in all the provinces were given broad administrative authority over public affairs, including education, the press and economic activities. Return to civilian rule would follow fundamental revision of the political order. In the meantime, the 1961 constitution, where it did not contradict the provisions of martial law, would remain in effect until replaced.[38]

Evren said the country had passed through a national crisis, and separatist forces and enemies, within and without, threatened its integrity; that Kemalism had been forgotten and the country left leaderless; and that the junta would correct this and enforce a new commitment to Kemalism, with Evren providing the necessary national leadership. Much of the country viewed the coup with relief, expecting that near civil war conditions would soon end. Indeed the rightist–leftist street clashes ended immediately. However, within months, the army opened a new front against Kurdish separatists, which gradually escalated by 1983, and it also suppressed Islamic political activism.

Turgut Özal was retained in the post-coup cabinet as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Economic Affairs. They decided to continue the economic policy he had planned under the former government. Özal negotiated with the IMF, World Bank, and EU. They released new credits and rescheduled former and more new debts. In this way, the state began a transition from an economy directed from above to an economy open to integration with world capitalism.

11. New ‘order’

The military regime forbade all strikes and union activities and disbanded the labor federations, imposed a strict curfew, and arrested more than 100,000 within eight months. Martial law authorities attempted to be evenhanded, arresting the rightist and religious as well as leftist members. Several newspapers were closed for publishing articles critical of the regime. By 1983, about 2000 prisoners had faced the death penalty. The trial of extreme rightist Mehmet Ali Ağca, who had tried to assassinate the Pope in 1981, revealed the extent of interactions between extremist groups and organized crime within Turkey and abroad.[39]

Universities were placed under the supervision of a newly created Council of Higher Education (YÖK). The junta held the power directly to appoint university rectors and deans, and purged hundreds of university faculty. Over the 1980s, the number of universities rose from 19 to 29. The right of university admission was broadened, effectively diluting the power of the old university faculties and the traditional elite classes, whose children made up the student bodies. In 1981, the centenary of Atatürk’s birth, the state arranged conferences, volumes of publications and the naming of numerous facilities and institutions – even a university – to commemorate ‘The Centenary’. Evren’s face next to Atatürk’s on banners and in public ceremonies linked him and his military regime to Atatürk and Atatürk’s regime.

In the autumn of 1981, the generals nominated the members of a consultative assembly, directly appointed by the NSC and martial law governors, to draft a new constitution. Its mandate was to purge the country of the effects of the 1960 coup, including the 1961 constitution, which was partly blamed for the fragmentation and polarization of Parliament, the judiciary, bureaucracy, and universities, for needlessly politicizing all public life, and for breeding the violence of the late 1970s. An annual holiday commemorating the 1960 coup was abolished.[40]

The new constitution was approved by referendum in 1982. While recognizing most civil and political rights, it laid heavy emphasis on the protection of the indivisible integrity of the state and national security, extended a measure of impunity for the extensive use of force during riots, martial law or a state of emergency, strengthened the presidency, and formalized the role of the military leadership. The president was charged with ensuring ‘the implementation of the constitution’ and ‘func tioning of the state organs’ and would become the guardian of the state, serving a single seven-year term with potentially wide powers. He would appoint the cabinet, the Constitutional Court, the military Court of Cassation, the Supreme Council of Judges and Prosecutors, and the High Court of Appeals. He would chair the National Security Council (NSC), now made a permanent body with the right to submit its views on state security to the Council of Ministers, who were required to give priority to the NSC’s views. Parliament again became a unicameral legislature. Any party short of ten percent of the national vote would not receive parliamentary representation. A new discretionary fund was created and put at the personal disposal of the prime minister, outside of the parliamentary budgetary process. Restrictions were placed on the press and labor unions. The State Security Court would rule on strikes, lockouts, and collective bargaining disputes. The government lost its mandate to restrict private enterprise. By a ‘temporary article’ appended by the NSC, General Evren became President, without being elected.[41]

The NSC forbade more than 700 former parliamentarians and party leaders from participating in politics for the next ten years. It shut down several newspapers for some time for failing to observe severe restrictions on political articles. Due to the brokerage firm and bank crisis in 1982, Özal left the cabinet. In 1983, the NSC permitted the formation of new political parties. Some new parties that looked like reincarnations of the old parties or were directed from behind the scenes by former leaders were barred from the elections and closed down. The NSC approved three parties: the Nationalist Democracy Party (NDP), led by a retired general, the Populist Party, headed by a former private secretary of İsmet İnönü, and the Motherland Party (MP), formed by Turgut Özal.[42]

President Evren did not hide his dislike of Özal but this only made his party an early favorite with a public very tired of the military. Evren’s stated preference for the NDP probably condemned it to a third-place finish. The MP won 45 percent of the vote and an absolute majority in Parliament.[43]

In 1980, on September 5, Fethullah Gülen spoke from the pulpit before taking leave of absence for the next twenty days because of illness. On September 12, the day of the military coup, his home was raided. He was not detained as he was not at home. He requested another leave of absence for 45 days. Then the house where he was staying as a guest was raided and he was detained. After a six-hour interrogation, he was released. On November 25, he was transferred to Çanakkale but, due to illness again, he was not able to serve there. From March 20, 1981, he took indefinite leave of absence.

By the third coup, the Turkish public appeared to have learnt a lesson. There was no visible public reaction. The faith communities, including the Gülen Movement, continued with their lawful and peaceful activities without drawing any extra attention to themselves. Gülen and the Movement avoided large public gatherings but continued to promote the service-ethic through publishing and small meetings. At this point, the Movement turned again to the use of technology and for the first time in Turkey a preacher’s talks were recorded and distributed on videotape.

In the years immediately following the coup, the Movement continued to grow and act successfully. In 1982, Movement participants set up a private high school in Izmir, Yamanlar Koleji.

12. The Özal years

For the decade before his death in 1993, Özal dominated Turkish politics. He set his sights on a fundamental shift in the direction of economic policy, to encourage exports and force Turkish products into a competitive position in the world market. His policy instruments were: high interest rates to combat inflation, gradual privatization of inefficient SEEs, wage controls, and an end to state industrial subsidies. Through the mid-1980s, the economy grew steadily: whereas in 1979, 60 percent of exports were agricultural products, by 1988 80 percent were manufactures; the annual inflation rate was lower than it had been; and the government completed large-scale infrastructural development projects.[44] Privatization proceeded very slowly, although the government was successful in breaking up state monopolies. The size of the bureaucracy was still considerable. Major cities grew as industry drew agricultural labor off the land. Economic liberalization rapidly benefited the largest industrial holding companies and some SEEs.

Having a clear-cut economic policy, and executing it with relative consistency, Özal skillfully managed the bureaucrats and the economy.[45]

By mid-1985 Özal was determinedly pursuing political liberalization as well. Martial law had been lifted in fifty of sixty-seven provinces. Eight provinces in the southeast remained under a state of emergency, and anti-terrorism measures stayed in place throughout the country. Turkey’s application for the full EEC membership that Özal championed was rejected in 1987. Economic liberalization did not automatically bring political liberalization with it. Özal succeeded in introducing new faces to political life in Turkey, but he was not allowed to normalize it completely or to exert civilian control over the military. By referendum, he let the former leaders of the former parties return to politics and called early elections for 1987. His Motherland Party won an absolute majority, 292 of the 450 seats; İnönü’s Social Democrat Party came in with 99 seats. Demirel’s True Path Party took 59 seats. No other party, including Ecevit’s or Erbakan’s, reached the threshold.[46]

An aspect of Özal’s liberalization was his encouragement of a role for Islam in public life. Özal understood that Islam was the source of the belief system and values of most Turkish citizens, and that it was excluded from the public sphere only with increasing awkwardness and artificiality. He said in 1986: ‘restrictions on freedom of conscience breed fanaticism, not the other way around.’[47]

In 1984, seeking to recruit religious sentiment against the influence of communism, the military regime required compulsory instruction in Islam in all schools. Picking up an initiative of the Menderes government, the regime sanctioned construction of 34 public Imam-Hatip training schools in one year. Özal’s government permitted the graduates of these schools to go on to the universities. Also, members of parliament and the cabinet were visible in attendance at mosques on holy days and other religious observances. Parliament permitted university students to cover their heads in the classroom. Advocates of the headscarf presented it as an issue of civil liberty: in a democracy, they argued, the individual ought to be free to wear any clothing within the limits of public decency; since the constitution guaranteed freedom of religion, laws forbidding the wearing of headscarves violated the citizens’ civil rights.[48] For its opponents, the headscarf was a reference to the veil that Atatürk had famously made a symbol of the ‘reactionary’ Islamic order. They claimed that wearing it was a political gesture directed against the secular state guaranteed by the constitution. In 1989, President Evren himself petitioned the Constitutional Court for a repeal of the new law permitting headscarves. Thousands of university students demonstrated throughout 1989 as the issue went into litigation, first being banned, and then re-permitted by an act of Parliament.[49] The Council of Higher Education (YÖK), in defiance of Parliament, banned it on university campuses.

Polarization became especially evident in the 1980s, as a new generation of educated but religiously motivated local leaders emerged as a potential challenge to the dominance of the secularized political elite. Assertively proud of Turkey’s Islamic heritage, they were generally skillful in adapting the prevalent idiom to articulate their dissatisfaction with various government policies. Certainly, through the example of piety, prayer, and political activism, they helped to restore respect for religious observance in Turkey.[50] In reality, the controversy about the headscarf on campuses is the larger question of the role of Islam in Turkish public life. The visibility of a new consciousness in the public sphere was disturbing for some laicist- Marxists, like Cumhuriyet columnist Akbal (1987):