Conjunctural factors

1. Conceptualizing the Gülen Movement

The questions discussed in this section are the ones most frequently asked about the mobilization by the Gülen Movement (GM) or about the counter-mobilization by its opponents at various conjunctures in Turkish history. The questions are:

1) whether the Gülen Movement is a civic initiative, a civil society movement;

2) whether it arises from a reaction to a crisis and/or is the expression of a conflict;

3) whether it is a sect or cult;

4) whether it is a political movement; and

5) whether it is an altruistic collective action.

These questions will be discussed to investigate how far epithets like civil, cultural, political, confrontational, conflictual, reactionary, regressive, exclusivist, sectarian, alienating, competitive, mediating, reconciliatory, pluralist, democratic, altruistic and peaceful can be appropriately used to characterize the Gülen Movement as collective actor or its action. The meanings of these terms are manifold and overlapping, but complementary and useful, and will help us to reach sound conclusions about the nature and potential of the Gülen Movement.

1.1. Is the Gülen Movement a civil society initiative?

Civil society is described ‘as an arena of friendships, clubs, churches, business associations, unions, human rights groups, and other voluntary associations beyond the household but outside the state [… providing] citizens with opportunities to learn the democratic habits of free assembly, non-coercive dialogue, and socioeconomic initiative’.[1] The terms ‘civil society sector’ or ‘civil society organization’ cover a broad array of organizations that are essentially private, that is, outside the institutional structures of government. They are also distinct from business organizations: they are not primarily commercial ventures set up principally to distribute profits to their directors or owners. They are self-governing and people are free to join or support them voluntarily.[2]

Despite their diversity, the services and institutions (SMOs ) provided by the Gülen Movement share important common features that justify identifying them in the social civic sector. They are not part of the governmental apparatus, and, unlike other private institutions, they are set up to serve the public, not to generate profits for those involved in them. In line with the definition given above, the SMOs embody a commitment to freedom and personal initiative; they encourage and enable people to make full use of their legal rights of citizenship to act on their own authority so as to improve the quality of their own lives and the lives of others in general.

The SMOs are not primarily commercial. They emphasize solidarity for service projects and collectively organized altruism. They embody the idea or ideal that people have responsibilities not only to themselves but also to the communities of which they are a part. Within the legal space as given, the Gülen Movement combines private structure and public purpose, providing society with private institutions that are serving essentially public purposes. The SMOs’ connections to a great number of citizens and their multiple belonging and professionalized networks within the civil society sector, enhance the Gülen Movement’s flexibility and capacity to encourage and channel private initiatives in support of public educational purposes and philanthropic services.

The Gülen Movement is distinguished by its substantial and sustained contribution to the potential of citizens to apply their energies to discover and implement new solutions following their own development agendas. It has boosted voluntary participation, multiplied networks of committed citizens in mutually trusting relationships, pursuing, through respectful dialog and collaborative effort, the shared goal of improving community services.[3] The Gülen Movement is thus an agent, on behalf of the country as a whole, for the accumulation of ‘social capital’. In explaining the term, Putnam (2000) says ‘social capital’ refers to connections among individuals – social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them. In that sense social capital is closely related to what some have called ‘civic virtue’. The difference is that ‘social capital’ calls attention to the fact that civic virtue is most powerful when embedded in a dense network of reciprocal social relations. A society of many virtuous but isolated individuals is not necessarily rich in social capital.[4]

Weller draws attention to the fact that ‘although often overlooked in the social and political constructs of modernity’, faith and faith-inspired organizations ‘form a substantial part of civic society and […] contribute significantly to the preservation and development of both bonding and bridging social capital’ in civic society volunteerism, the third sector and democracy.[5] The voluntary aspect of association with it is an important dimension of the Gülen Movement.[6] Individuals freely join associations and services of their choice, and they are also free to exit, without cost. Whether the underlying motivation for such voluntary participation is self-fulfillment, selfexpression, self-development or something else, it is expressive of the individualistic nature of the concept of civil society.[7]

The fact that, as a thoroughly civic, autonomous initiative, the Gülen Movement is situated entirely outside the conventional channels of political representation – party, government, state, etc. – does not mean that it therefore stands in some way against the political, governmental or democratic system. This would be a grave misreading of the reality of the diffused civic networks of collective action. Through the non-profit-oriented management of its educational and cultural institutions, the Gülen Movement distinguishes itself sharply from political actors and formal state institutions and agencies. Its forms of collective action are multiple, variable and simultaneously located at several different levels of the social space. They do not contend with, or for space in, government or state institutions or agencies.[8] They deal with human beings individually in the public space through independent, legally constituted civic organizations.[9] The Gülen Movement’s field of action – the origin, source and target of what it does – is the individual human being in the private sphere.[10] The natural consequences of this action extend to the civil–public sphere. Its approach is ‘bottom–up’, namely, transforming individuals through education to facilitate the consolidation of a peaceful, harmonious and inclusive society as a result of an enlightened public sphere. It is not the ‘top–down’ approach characteristic of state or government agency. That is indeed the rationale for Gülen’s emphasis on the primacy of education among the Gülen Movement’s commitments:

As the solution of every problem in this life ultimately depends on human beings, education is the most effective vehicle, regardless of whether we have a paralyzed social and political system or we have one that operates like clockwork.[11]

In short, the Gülen Movement’s work demonstrates a shift in orientation from macro-politics to micro-practices.[12] While the Gülen Movement’s origin and services arise from a civil-society-based faith initiative, its discourse and practice affirm the idea that religion and the state are and can be separate in Islam, and that this does not endanger the faith but, in fact, protects it and its followers from exploitation and may strengthen it.[13] After his analysis of the transnational social movements originating from Muslim communities, Hendrick concludes:

The Gülen Movement emerged as the most successful purveyor of Turkey’s improvisation of Islamic modernity, a civil/cosmopolitan Islamic activist movement that seeks to realize its goals of global transformation via ‘moral investment’ in the global economy, ‘moral education’ in the physical sciences, and moral convergence with ‘other’ groups via tolerance and dialogue.[14]

The common features shared by its SMOs justify identifying the Gülen Movement as a civic initiative and a civil society movement.

1.2. Is the Gülen Movement a reaction to a crisis and/or an expression of a conflict?

To answer that question, it is necessary first to distinguish the terms ‘crisis’ and ‘conflict’.

A crisis denotes breakdown of the functional and integrative mechanisms of a given set of social relations in one sector of the system or another. A crisis arises from processes of disaggregation of a system, related to dysfunctions in the mechanisms of adaptation, imbalances among parts or subsystems, and paralyses or blockages therein. A conflict, on the other hand, is a struggle between two actors seeking to appropriate or control resources regarded by both as valuable; the actors have a shared field of action, a common reference system, something at stake between them to which both, implicitly or explicitly, refer.

Conflicts are conceptually distinct from crises. In conflicts the adversaries enter into strife on account of antagonistic definitions of the objectives, relations, and means of social production at issue between them. Whereas an antagonistic conflict manifests as a clash over control and allocation of resources deemed crucial by the concerned parties, a crisis provokes a subsequent reaction on the part of those who seek to correct the imbalance that has happened in the system. The difference between a crisis and an antagonistic conflict is a significant one, one that can help to determine if the collective actor – in this case the Gülen Movement – is conflictual, contentious, reactionary, claimant or otherwise.

The research scholar Webb identified education and health as the major crises in Turkey since the period of the Ottoman state: the problems ‘continually grew larger during the republican period and were even manipulated for political goals’. What aggravated these crises was, in her judgment, the fact that ‘ideological and political concerns rather than logic and science ruled almost all the decisions made in the field of education’. During this time, Turkey did not achieve anything of note in this field in the international arena. ‘To the contrary, the universities, which should have done high-level scientific work, each became a point of political focus and they were in the forefront of the three military coups d’état.’

Interviewee Abdullah Aymaz argued that the dominant interest groups define movements in Turkey without referring to any crises, as if there had never been dysfunctions or faults in the operation of the system.[15] Yet, the Gülen Movement, in the face of the crises related to certain policies (or lack of policies) in Turkey, does not draw upon logic and action based on victim-blaming or systemblaming, or on the adoption of an injustice frame, or on opposition to the ruling system and the dominant interest. Rather than cursing the darkness, it prefers to strike a light against darkness, ignorance, backwardness, disunity, unbelief, injustice and deviations. So it does not concern itself with politically challenging the legitimacy of power or the current deployment of social resources.[16]

Therefore, for Aymaz, the Gülen Movement cannot be defined as a conflictual or confrontational reaction, and, in this sense, the Gülen Movement cannot be seen as a pathology of or antithetical to the social system. Similarly, Ünal and Williams (2000:iii) hold that Gülen and the Gülen Movement do address and try to deal with problems or crises – problems such as the attempted politicization of religion, societal and sectarian tensions and exploitation thereof to keep Turkey off-balance, and undesirable activities such as fundamentalism, dogmatism and coercion – but not specific individuals or groups or political parties or the state.

On the other hand, might some crisis have facilitated the Gülen Movement’s course of action, and contributed to its emergence or visibility in the public space? The appearance of the Gülen Movement has been linked by some commentators to certain conjunctural factors, the most frequent link[17] being to the economic and political liberalization policies of Turgut Özal, who dominated the Turkish political scene for a decade – first as prime minister (1983–89) and then as president (1989–93). Those policies led to socioeconomic processes, like the movement of people to new urban centers, and the establishment of new universities and consequent expansion of mass education. These processes are said to have brought a new consciousness into politics, which prompted people to ‘question the state ideology, participate in formal politics and in the multiple networks of the faith-inspired communities’. Then, it is said, consciousness informed ‘frameworks to discuss identity, morality and justice in society’.[18] While these explanations contain a small kernel of truth, they are reductive and miss the reality and meaning of the Gülen Movement in this period.

An example of such reductionism is Yavuz’s claim that the emergence of the Gülen Movement is attributable to the increased migration from the countryside to the cities, the urbanization, industrialization and modernization of Turkey during the Özal decade.[19] This is at best a very partial explanation, and unsatisfactory because it fails to take account of or distorts key aspects of the Gülen Movement and its history.

Social scientist Jones has shown that what is common to all reductions is that one phenomenon is explained in terms of another of a different nature, one thought to be simpler or more fundamental, so that ‘our desire for understanding at least the reduced phenomenon is satisfied.’[20] Although different kinds of reductionism do not proceed in exactly the same way, an example would be reducing the social dynamics of religions to economic conditions. ‘This process may be a direct substitution of realities or the specification of the real causes at work in the phenomenon.’ Jones adds:

Structural reductions of religious phenomena to non-religious sociocultural phenomena (even if established) cannot rule out that there may yet be more to religion – something other than being a purported sociocultural cause – and so cannot entail the substantive reduction of religion to only sociocultural phenomena. In particular, it would not rule out the possibility that religious experience involves an experience of other realities than those involved in social scientific theories.

Similarly, Mellor maintains that social realities are much more complex than economic models allow, that the real social significance of faith or religion needs to be acknowledged as a causal power affecting people’s views, choices and actions:

Religious influences are located at the heart of all societies rather than in the private or epiphenomenal ‘sub-systems’ envisaged by secularization theorists. […] This underlines the importance of the specifically religious differences for the development of society, and points towards some of the dangers in trying to explain away religious factors through forms of economic and political reductionism.[21]

It is surely obvious that a collective actor like the Gülen Movement cannot have come abruptly into being, with educated, trained adherents ready to seize on the opportunities presented by the opening up of the system or political structure at a specific time and place. Social movements take time to develop; they do not come ready made. In any case, as sociologist Koopmans has argued,[22] the availability of political opportunities does not automatically and promptly translate into increased action and is insufficient to account for the emergence of a collective action and actor. For an organized collective action as large as the Gülen Movement, there has to be, already in place, a sufficient contingent of people with the necessary intellectual and professional skills, and the readiness and will to be employed, before a particular historical conjuncture opens up a window of opportunity.

Linking the Gülen Movement to Özal’s liberalization policies is, at best, an account of the structural conditions that define the action, it is a deficient, reductionist explanation insofar as it neglects to examine the actor itself – in terms of internal factors for example – and so fails to account for the types of behavior observed. In point of fact, the structural conditions explanation is itself of doubtful value, generally and particularly. Generally, because a collective actor or action does not automatically spring from structural tensions or conditions: ‘Numerous factors determine whether or not this will occur. These factors include the availability of adequate organizational resources, the ability of movement leaders to produce appropriate ideological representations, and the presence of a favorable political context.’[23] And particularly, because the example of Özal invalidates the argument since Özal himself was from the faith communities,[24] from the multitude of people already educated, qualified and holding roles and status in Turkish society and the state structure at that time. A single individual could not, by coming to a higher position one day, have produced people like that in such a short period of time, let alone a movement like Gülen’s, when there were already other state bodies functioning independently and when there was in place a large and strong protectionist opposition to what Özal said, planned and carried out.

The hypothesis that political structure opportunities alone account for the existence of a particular group or collective actor is also disproved by asking the obvious question: If Özal and political conjuncture played such a formative role in the emergence of the Gülen Movement, why did the same opportunities not lead other actors to achieve comparable public visibility, resonance and legitimacy? As social scientists Edwards and McCarthy explain: ‘the simple availability of resources is not sufficient; coordination and strategic effort is typically required in order to convert available pools of individually held resources into collective resources and to utilize those resources in collective action.’[25] The reality is that the faith-inspired communities had managed to utilize all the different forms of communication networks and media and, as entrepreneurs independent of state subsidies, had proved themselves successful and profitable in foreign-exchange-earning export industries.[26] Such financial and business acumen cannot be acquired all of a sudden following one person’s accession to political power. In short, the explanation is not a careful evaluation of the conjuncture but social reductionism – it ignores the existence of informal networks, of everyday solidarity circles; it disregards ‘the density and vigor of the networks of belonging, and the associative experiences that individuals have accumulated’.[27]

The mobilization resources of the Gülen Movement were present at the time, ready to be directed towards new goals because already in place. Had they not been, the situation could not have created them, nor could they have benefited from the situation to redirect and reshape their action.

The informal networks and resources, all the heritage, present in the movement need to be taken into consideration. Sociologist Kömeçoğlu (1997) highlights the role of non-visible networks – a movement ‘incubates’ before it emerges into the public. He distinguishes between the discovery of the movement by the mass media and its organizational and cultural origins. Distinguishing between ‘latent’ and ‘visible’ phases in the formation of the Gülen Movement, he deems it necessary to explore the cultural networks that existed before its public appearance. Della Porta and Diani (1999) support Kömeçoğlu’s claim with the argument that adequate organizational resources necessarily precede the mobilization of a collective actor.[28] Thus, prior to the 1980 military coup, Gülen Movement participants had already responded to the crisis in education and the contraction in the field for the expression of moral concerns by setting up institutions such as student halls of residence, university entrance courses, teacher associations, publishing houses and a journal (see the outline of events in Chapter 2.2.8, pp. 30–33). In short, the claim that the Gülen Movement emerged as a consequence of Özal’s economic liberalization is simply a reductionist account and accordingly deficient even as a partial explanation or definition of the Gülen Movement.

The Gülen Movement did not emerge because of, or as the expression of, any conflict, let alone a conflict between the religious-minded and the secularists in Turkey.[29] Webb argues that although the protectionist interest group ideologically frames any effort from the faith-inspired communities as reactionary or fundamentalist, the Gülen Movement has never been mentioned in connection with any anarchy, terror or misuse of office. She adds that any such ‘framing’ has no concrete basis and has been rejected by the public, and indeed by the courts also. Hendrick maintains that the Gülen Movement does not pose any threat to existing political or economic institutions: ‘However conservative, however devout, the Gülen Movement is not fundamentalist.’[30]

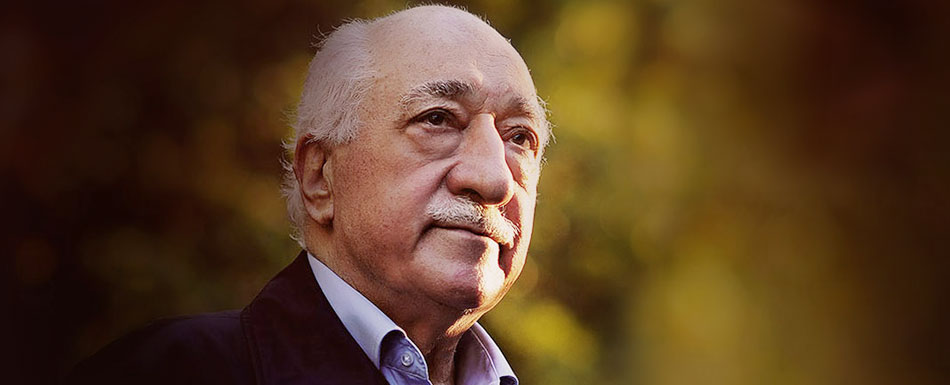

A conflict, as we defined it earlier, is the opposition of two (or more) actors vying for control of social resources valued by them.[31] Fethullah Gülen takes no part in this. He argues: ‘for a better world, the most effective path must be to avoid argument and conflict, and always to act positively and constructively’;[32] and: ‘in the modern world, the only way to get others to accept your ideas is by persuasion’; ‘those who resort to force as intellectually bankrupt; for people will always demand freedom of choice in the way they run their affairs and in their expression of spiritual and religious values.’ While it still needs to be improved, ‘democracy is now the only viable political system, and people should strive to modernize and consolidate democratic institutions in order to build a society where individual rights and freedoms are respected and protected, where equal opportunity for all is more than a dream’.

Fethullah Gülen himself neither approves nor ever uses the terms ‘Gülen Movement’ or ‘Gülen Community’. He prefers the action to be called the ‘volunteers service’ because this does not connote any contentious otherness, political separatism or conflictual front. He insists that the Gülen Movement does not and must not involve conflict; the volunteers service must be offered within the framework of the following basic principles: (1) constant positive action that leaves no room for confusion, fighting, and anarchy; (2) absence of worldly, material, and other-worldly expectations in return for service; (3) actions, adorned with human virtues that build trust and confidence; (4) actions that bring people and society together; (5) sustaining patience and compassion in all situations; (6) being positive and action-oriented, instead of creating opposition or being reactionary. Offered in this spirit, Gülen says, volunteer services can be said to be seeking only God’s approval. He encourages all individuals in sympathy with his opinions to serve their communities and humanity in accord with this peaceful, nonconflictual, non-confrontational and apolitical stance.

Ünal and Williams argue that many people from all walks of life and different intellectual backgrounds are attracted to and participate in this service because it permits no expectation of material and political gain and because it is not conflictual. The types of service Gülen mentions – education, health, intercultural and interfaith dialog, cooperation of civilizations – require action, and concern relationships in the everyday lives of all members of society and humanity. The sociologists’ term for this level is the lifeworld. If an action occurs that breaks the rules at the lifeworld level, it is described as conflictual. In conflictual actions or networks, action is taken by simpler and small ‘cells’ against the rules that govern social reproduction in everyday life. These cells go on to generate networks of conflictual social relations and a variety of forms of resistance.[33] Naturally there are forms of such popular resistance in Turkey, but this activity or behavior is absent in the Gülen Movement. Gülen asserts that conflictual or reactionary action cannot reach its goals precisely because it typically offers extremism and violence and gets counter-extremism and counter-violence in return:

Reactionary actions – or movements, no matter how powerful they are – cannot be successful [in] achiev[ing their] purposes, for balance and moderation cannot be maintained in them. Contrarily, they prove to be more harmful […] as people fall into extremism. They thereby cause reactions on the other side. Violence ensures counter-violence from the others, too. What is essential, what ought to be, is positive action.

Aymaz maintained that none of projects in which Gülen Movement participants are involved ever break the rules of society, nor do they try to change “the rules of the game” in whatever field they concern. This is supported by the results of surveys conducted by independent organizations, by the recognition and acceptance of the Gülen Movement’s educational institutions abroad, and by the failure of the legal actions taken by the protectionist elite in Turkey against Gülen:

The Gülen Movement does not do anything which prevents the system from maintaining its set of elements and relations that identify the system as such. Since the Gülen Movement participants and their projects do not breach social limits, the system can acknowledge, or tolerate, them without altering its structure. In this sense, the Gülen Movement has order-maintaining orientations. However, it does not come into being through consensus over the rules governing the control of valued resources. The intention of the Gülen Movement is not to protect the rules and procedures to protect the status quo governing the control of valued resources, any more than it is to challenge them.[34]

Interviewee Ergene stated that the Gülen Movement cannot be described as marginal as it did not come into being to react to the control and legitimacy of the system or its established norms, nor is it a consequence of the inadequate assimilation by some individuals of those established norms. Moreover, the Gülen Movement does not identify a social adversary and a set of contested resources or values. Within the Gülen Movement people express disapproval of actions or traits such as immorality, unbelief, injustice, provoking hostility and violence, and deviations, but disapproval or hatred is not expressed of the people who engage in them. Ergene explained that the protectionist elite within the establishment have attempted to obscure this and the Gülen Movement’s achievements and have thus been led into the reductionism of seeing the Gülen Movement’s philanthropic services and innovative potential as subversive:

Based on Islamic teachings[35] Gülen encourages people to services which are not an opposition [to] interests within a certain normative framework nor do they seek to improve the relative position of the actor so that the actor will be able to overcome functional obstacles in order to change authority relationships. This kind of [altruistic] behavior can be defined as competition for the good or better. It concerns not contending interests but presenting the likely best that can be done for the betterment of the conditions of society and humanity.

Melucci[36] concurs with Ergene that such competition accepts the set ‘rules of the game’ and is regulated by the rights people are entitled to and by the interests that operate within the boundaries of the existing social order. Such competition is indeed different from those forms of solidarity action which force the conflict to the point of infringing the rules of the game or the system’s ‘compatibility limits’.

Interviewee Çapan also stated that the Gülen Movement does not breach the system limits in order to defend the social order, as in the case of ultra right-wing counter- or fascist- movements in history. The Gülen Movement does not claim, compete for, or raise conflict over, something within the state organizational or political system.[37]

‘After 9/11, a lot of groups said they are moderate and changed their rhetoric,’ said Baran. […] ‘But the Gülen Movement for the last 30 to 40 years has been saying the same thing. They have not changed their language because they want to be okay now.’[38]

Since the Gülen Movement is not a struggle or mobilization for the production, appropriation, and allocation of a society’s basic resources, nor engaged in conflict over imbalances of power and the means and orientation of social production, it is not materialistic or antagonistic. Any hypothesis linking the Gülen Movement to capitalist production or political positions and institutions obscures the cognitive, symbolic, and relational components that give the Gülen Movement its distinctive character.

The Gülen Movement does not dispute the shared rules and the processes of representation, or how normative decisions are made through democratic institutions. It aims for the internal equilibrium of society, for exchange among different parts of the system, and for roles to be reciprocally assured and respected so that social life, fairness and the material and non-material prosperity of individuals are maintained and reproduced through interaction, communication, collaboration and education. These relations allow individuals to make sense of themselves, of this world and its affairs, and of what lies beyond.

Undoubtedly, relations and meanings, goals and interests transcend individuals. But the Gülen Movement takes no direct interest in institutional change or the modification of power relationships. Rather, it aims to bring change in the individual, in mind-set, attitudes and behavior. Many forms of the voluntary and altruistic community action undertaken by Movement participants correspond to everyday life and are strictly cultural in orientation, not political. Aymaz, when asked if the Gülen Movement could be considered a political movement, distinguished two types of actions or actors:

The political one presses for a different distribution of roles, rewards or resources and therefore clashes with the power imposing rules within the structural organization of state; and the non-political one strives for a more efficient functioning of the apparatus or, in fact, for that apparatus’ more successful outcomes, without exceeding the established limits of the organization and its normative framework.[39]

In this sense, Aymaz is saying, the Gülen Movement cannot be called a claimant movement either, since it is not seeking to defend the advantages enjoyed by a separate group or to mobilize on behalf of an underprivileged ethnic, religious, social or political group to get for it a bigger piece of the ‘cake’ of public funds or other resources.

Interviewee Çapan was clear that the Gülen Movement neither mobilizes for political participation in decision-making, nor fights against the state ideology, nor pretends to have a bias or tendency so as to get access to decisionmakers. Movement participants have contributed to the opening-up of new channels for the expression of previously excluded demands like intercultural and interfaith dialog and co-operation (rather than conflict) between civilizations, yet in doing so, they do not in any way push their action of service outside the limits set by the existing norms and Turkish political system. Nor do they seek to change the direction of the state’s development policy or otherwise intervene in its decisions or actions. Çapan added that not every publicspirited action is political or antagonistic; rather, there are social, cultural, cognitive, symbolic and spiritual dimensions of such action that can never entirely be translated into the language of politics.[40]

Snow and colleagues[41] class political actors as interest groups and define them in relation to the government or polity, whereas the relevance and interests of social movements extend well beyond the polity to other institutional spheres and authorities. Melucci holds that political actors engage in action for reform, inclusion in and redefinition of political rules, rights and boundaries of political systems; they therefore interact with political authorities, negotiate or engage in exchanges with them. They strive to influence political decision-making through institutional and sometimes partly non-institutional means. Non-political actors, by contrast, address issues in a strictly cultural form or cultural terms, and bring issues forward into the public sphere. They choose a common ground on which many people can work together. They name issues and then let them be processed through political means and actors.[42]

According to the definitions above, the Gülen Movement falls into the category of cultural or social actor rather than political actor. Although political action is legal, legitimate and indispensable for democracy in a complex system like Turkey, the Gülen Movement avoids formal politics, and acts at its own specific level within the limits to which it is entitled by law, aiming at well-defined, concrete, and unifying goals and services.[43] In particular, as Alpay (1995a) has argued, Gülen ‘separates religion from politics, opposes a culture of enmity that can polarize the nation’.[44]

For the Gülen Movement, institutions and the market are not traps to be avoided but instruments to be utilized to the extent that they achieve the common good. In this way it strives to perform a modernizing role within institutions and societies. It contributes to the creation of common public spaces in which an agreement can be reached to share the responsibility for a whole social field beyond one party’s interests or positions. Greek Patriarch Bartholomew confirmed this:

In Turkey, Christians, Muslims and Jews live together in an atmosphere of tolerance and dialogue. We wish to mention the work of Fethullah Gülen, who more than ten years ago began to educate his believers about the necessity for the existence of a dialogue between Islam and all religions.[45]

The moral dimension of these issues and the successful provision of services that transcend any one party’s interests or positions, raise awareness and so fuel reflection and discussion. That is, as it were, the herald of a cultural change that is already well on its way in Turkey and elsewhere. As Fuller points out, this change is perceived by some militant secularists in the army and the old elite structure as an assault against specific interests, an attempt to shift power relationships within the political system, and to acquire influence over decisions. However, Fuller argues, the Gülen Movement promotes an apolitical, highly tolerant and open regeneration of faithinspired values, focused on education, democracy, tolerance and the formation of civil society: the Gülen Movement ‘represent[s] a new Anatolian elite, comfortable with its Islamic heritage while striving to be modern, technologically oriented, and part of the European system as long as that does not mean a total loss of Islamic identity.’[46]

1.3. Is the Gülen Movement a sect or cult?

What distinguishes Gülen and the Gülen Movement from cults and sects? If the distinction is clear why is it said that the Gülen Movement is a sect?

Turkey is a secular state in which freedom of conscience and association are conceived in such a way that religious communities and religious orders (because not regulated by the state) do not officially exist. The Turkish Constitution’s commitment to laicism means that people can be (and many people have been) prosecuted for affiliation to and support of religious orders or sects. Yavuz and Esposito argue that ‘the sharp division between moral community and the political sphere is the source of many problems in Turkey. As the Turkish political domain does not provide an ethical charter, the moral emptiness turned the political domain into a space of dirty tricks, duplicity and the source of corruption’.[47] Politics in Turkey is, regrettably, based on what are euphemistically called ‘protective relationships’, for the sake of which the concepts of both religion and secular democracy are misused.[48] Smith comments wryly, ‘[Critics] say that Ankara [i.e. the hub of establishment politics] has cultivated a seamless web of internal and external threats – some real some imagined – to keep the enterprise afloat.”

The contraction of the field in which moral values can be expressed, combined with the inability or unwillingness of the authorities to deal with acute social crises, prepares people to turn to SMOs.[49] Because the people needed them, faith communities and religious orders not only survived, they have revived and gained prominence in Turkey. Alpay explained this succinctly: ‘modern institutionalization and organization in Turkey remain behind, backward, whereas religious brotherhood and solidarity, basic forms of social organization, continue.’[50] Indeed, those basic forms of organization, bottom–up, civic, faith-inspired initiatives, constituted the necessary social capital and resource for modernization in the country. That success was nevertheless viewed by the protectionist elite with suspicion and described as a potential or actual threat to the foundations of the state.

As the most conspicuously successful and popular effort to generate the social capital that the state was unable to generate, the Gülen Movement and Gülen himself have been particularly targeted. One of the devices to delegitimize them and their services is the accusation that ‘albeit non-political’ they are a sect, backward, and thus subversive. Yet, while accusations of this kind have been plentiful, evidence of (under Turkish law) unlawful association, action or conspiracy has been non-existent. Not a single person from the Gülen Movement has so far been convicted of any of the false charges laid against them by ideologically motivated prosecutors and the protectionist groups behind them. Webb, after listing almost one hundred lower court hearings and judgments concerning Gülen himself, concludes: ‘In the light of the relevant court decisions, and according to the verdicts given, experts appointed by the courts and the courts, the major conclusion is that the allegations and such similar claims [about him] are untrue, baseless and unsubstantiated.’ Webb adds that the authoritative bodies found that there was no sign in his works of supporting the interests of a religious sect, seeking the establishment of a religious community, or using religion for political or personal purposes, or of any violation of basic government principles and order. Gülen’s works consist of explanations of the Qur’an and Hadiths, religious and moral advice, writings that encourage the virtues of good, orderly citizens, what any government would approve and wish for.

Aymaz explained why the Gülen Movement cannot be described as a sect:

The Gülen Movement has never ever attempted to form a distinct unit within Islam. [It is] not a distinct unit within the broader Muslim community by virtue of certain refinements or distinctions of belief or practice. Neither is it a small faction or dissenting clique aggregated around a common interest, peculiar beliefs or unattainable dreams or utopia. The Gülen Movement is already a well-established and transnationally recognized diffused network of people. The Gülen Movement has no formal leadership, no sheikhs and no hierarchy. They don’t have any procedures, ceremonies or initiation [to pass] in order to be affiliated or to become a member.

Aymaz further explained that in the wider society, Movement participants are neither viewed nor act as any kind of closed, special group:

Movement participants, with their words, projects and actions, have proved themselves not to have any strongly held views or ideology that are regarded as extreme by the majority in Turkey and abroad. They have never been regarded as heretical or as deviant in any way by the public, in the media or in the courts. They have not been accused of being different from the generally accepted religious tradition, practices or tendencies. All movement participants are educated, mostly either graduates or post-graduates, serving voluntarily. These volunteers work by themselves, thousands of miles away from a specific doctrine or a doctrinal leader.[51]

Hermansen explains why the Gülen Movement cannot be called a sect or cult in similar terms:

Tibi deprecatingly referred to the Gülen Movement as a Sufi tariqa including as a critique that Gülen functions as the shaykh (Sufi master). Agai concludes that this is a misrepresentation because unlike classical tariqa, there is no requirement of initiation, no restricted or esoteric religious practices, and no arcane Sufi terminology that marks membership in the Gülen Movement. Ergene also strongly disagrees with the characterization of the Gülen Movement as a tariqa in any classical social or organizational sense.[52]

If the Gülen Movement cannot be labeled a cult or sect on account of its actions, can it be so labeled on account of participants’ relations to its founding figure, Fethullah Gülen? This is the issue of ‘charisma’, and the associated process of ‘charismatization’. Charismatization makes the group-leader in the eyes of its members a special, even a super-, being; it entails myths about his childhood, sacralized places, holy objects he has touched, etc. A picture is built up of this super-being who is nevertheless prepared to come down to the level of ordinary people. Charismatization makes the groupleader unaccountable, unpredictable, arbitrary in the exercise of authority and prone to abuse of power:

The authority that is accorded by the followers [of the] charismatic [leader], insofar as it is not bound by rules or by tradition and the charismatic leader has the right to say what the followers will do in all aspects of their life – whom they will sleep with […] marry, whether they will have children, what sort of work they will do, in what country they will live – perhaps whether they will live – and what toothpaste they will use. It really can cover anything; and it can be changed at a moment’s notice.[53]

Fethullah Gülen has been visible in public life through his speeches, actions, and projects since he was sixteen years old as preacher, writer and the initiator of civil society action. He has not led anyone into any absurdities, deviations, violence, killings, suicides or abuse of any sort. He has not presented any attitude of unaccountability or arbitrariness in his thoughts or actions. In Turkey a very few marginal, ideologically motivated individuals and groups have opposed his worldview and projects, yet none so far has substantiated any accusation like that. This is a good indication that Fethullah Gülen and the Gülen Movement are nothing like the sects, cults or new religious movements studied by Barker and others.

We set out earlier (§3.2.5, pp. 79–83) how and why the reflexivity of the Gülen Movement is so high. Movement participants have a clear definition of the services, the field of their action, the goals and the instruments used to achieve them, and as a result, what to expect and not to expect in return for what they are doing. The Gülen Movement also has much accumulated experience, which it is very successful at imparting to its participants and to those outside the Gülen Movement. The Gülen Movement therefore does not experience a gap between unattainable goals and expectations and rewards. The clarity about general goals and particular objectives – the attainability of its projects – the stress on and the adherence to legitimacy of means and ends– the accountability of how the projects are delivered – distinguish Gülen and the Gülen Movement from cults and sects in a clear way.[54]

In the Gülen Movement, the rewards to be expected as a result of services provided are strictly ‘from God’.[55] The Gülen Movement does not offer selective incentives (atomized cost–benefit calculations) to attract participants in the pursuit of collective goals. Direct participation in the services itself provides the motivation – to embody highly symbolic, cultural, ethical and spiritual values, rather than to accrue worldly goods and material gains. Kuru notes: ‘Gülen is against the kind of rationalism that focuses on egoistic self interest and pure materialistic cost–benefit analysis.’[56]

Fethullah Gülen himself has said: ‘If I were to prefer this world, to prefer to be at the top of the State, I would have looked for a position in certain places where such preferences could be realized.’ He never did so, having lived his whole life, including youth, as an ascetic. Recalling his youth when worldly prospects were available to him, he said: ‘If this person refused all the opportunities that came to his doorstep and rather headed for his wooden hut in his youth, how could he have such desires now when he spends every night “as if this were my last”? I think all of these accusations [of seeking position or power] arise from [the accusers’] feelings of hatred.’[57]

Because motivation and incentivization are realized through the relational networks and the services provided altruistically alongside others, it ties the individuals together. The cohesiveness of the group, in contradistinction to cults, does not derive from belonging to it. Belonging is not for its own sake, turned inward, but for the service of others, i.e. always looking outward. Gülen often refers to the maxim: ‘An individual should be among the common folks like any ordinary individual, yet with the constant consciousness that he or she is with God and under His constant supervision.’ This means ‘living among people, amidst multiplicity’.[58] Therefore, unlike sects or cults, Movement participants prefer being with and for people, not avoiding them; they do not draw back into themselves and break off relations with social partners, or sever relations with the outside, nor renounce the relevant and feasible courses of action. To the contrary, Gülen stresses the current realities, the interdependency of communities that has emerged with the modern means of communication and transportation – the world become a global village. He teaches the awareness that any radical change in one country will not be determined by that country alone because this epoch is one of interactive relations, and nations and peoples are more in need of and dependent on each other, a situation that requires closeness in mutual relations. Therefore, people should accept one another as they are and seek ways to get along with each other. Differences based on beliefs, races, customs and traditions are richness, and should be appreciated for the common good through peaceful and respectful relationships. Gülen adds:

This network of relations, which […] exists on the basis of mutual interest, provides some benefits for the weaker side. Moreover, owing to advances in […] digital electronic technology, the acquisition and exchange of information is gradually growing. As a result, the individual comes to the fore, making it inevitable that democratic governments which respect personal rights will replace oppressive regimes.[59]

In another sense also, the Gülen Movement is not closed off from the world – it knows that it needs to be in the world in order to learn from it. Fethullah Gülen explains: ‘People must learn how to benefit from other people’s knowledge and views, for these can be beneficial to their own system, thought, and world. Especially, they should seek always to benefit from the experiences of the experienced.’[60] It seems unlikely that individuals in a movement who have been reading and listening to Gülen would be in a sectlike relationship or structure. Instead, Gülen urges inclusivity and openness to other people: ‘Be so tolerant that your bosom becomes wide like the ocean. Be inspired with faith and love of human beings. Let there be no troubled souls to whom you do not offer a hand, and about whom you remain unconcerned.’[61]

The Gülen Movement does not have an ideology that posits an ‘adversary’ that it then makes an object of aggression, and to which it denies any humanity or rationality or potential for good. It systematically and consistently refuses to activate negative or destructive processes. It has for that reason sometimes been criticized for passivism. On the contrary, however, it encourages a higher motivational level and opens the way for individual and collective responsibility and mobilization. Gülen teaches that the principal way to realize projects is ‘through the consciousness and the ethic of responsibility. [… As] irresponsibility in action is disorder and chaos, we are left with no alternative but to discipline our actions with responsibility. Indeed, all our attempts should be measured by responsibility.’[62]

This consciousness and ethic of responsibility nurtures individual upward mobility in the SMOs established with Gülen’s encouragement. ‘[These] institutions have a corporate identity and their management is in the hands of real people. However, having been appointed as a manager through a social contract, these people are not allowed to utilize the institutions for their own benefits. Those who are now unable to work actively in the movement give over their role to the young people who will carry the torch of the altruistic services of the movement.’[63] Hermansen recalls how a senior participant in the Gülen Movement described its activism in terms of a relay race in which the current generations are running and passing the torch on to the next cohort to take it onward and higher.

Individual upward mobility is for all and always possible in the Gülen Movement because entry and exit, or commitment and withdrawal, are always voluntary and always open. A competitive spirit is also encouraged and predominates over the primary solidarities. Individuals are employed at the SMOs on the basis of professional qualifications rather than on the basis of Movement experience or ‘seniority’.[64] These features all prevent the rise of any dogmatic leaders, ideologues, rites, or exclusivist functions within the Gülen Movement. They also prevent the Gülen Movement from constructing an idealized self-image with exclusive values and symbolic resources and taking refuge in myth.

The Gülen Movement does not have or seek to have private sacred texts exclusive to itself, or develop special rituals and priestly functions, or special costumes or gestures or insignia, or other closed identity devices. It does not offer outcomes or rewards unattainable by the ordinary means of human effort in the real world. It does not seek sacral celebration of the self in an abstract and anachronistic paradigm.[65] The Gülen Movement’s action is not directed against anyone, real or mythical: it has no fantasized ‘adversary’ to blame if there is any shortfall in outcomes. Rather, any failure must be socially defined within the actors’ frame of reference and responsibility. Fethullah Gülen identified the three major problems as the basis of all the trouble in modern Turkey: ignorance, poverty, and internal schism (social disunity). To these he added:

Now to these have been added cheating, bullying and coercion, extravagance, decadence, obscenity, insensitivity, indifference, and intellectual contamination.[66] A lack of interest in religious and historical dynamics, lack of learning, knowledge, and systematic thinking […] ignorance, stand as the foremost reason today why Turkey and the region is so afflicted with destitution, poverty.[67]

The limits of the reference field of the Gülen Movement (its principles and goals) do not permit any sort of aggressive and non-institutionalized mobilization, impractical and incompatible demands or expectations, or anything transgressing boundary rules – either in the Turkish or the international arenas – that could trigger conflict.[68] Movement participants are encouraged to reflect upon and compare their action in different situations at different times – an open process of working out costs and benefits, of measuring effort and outcomes, that enables them to criticize and amend policy, to predict likely outcomes, to learn from mistakes, etc. In this way, the institutions, the services given and their success, do not belong to any single individual and moreover remain oriented outwards to the real world.

Education, as we have emphasized, is the Gülen Movement’s chief priority. In Gülen’s view it is not only the establishment of justice that is hindered by the lack of well-rounded education, but also the recognition of human rights and attitudes of acceptance and tolerance toward others: ‘if you wish to keep the masses under control, simply starve them in the area of knowledge. They can escape such tyranny only through education. The road to social justice is paved with adequate, universal education, for only this will give people sufficient understanding and tolerance to respect the rights of others.’[69] The education supported by the Gülen Movement is oriented to enabling people to think for themselves, to be agents of change on behalf of the positive values of social justice, human rights and tolerance.[70] This again sharply distinguishes the Gülen Movement from the tendency of cults to be oriented inward and to demand conformity from group members (of which the private rites, insignia, etc., are a badge).

The style and content of education is another distinguishing factor. Gülen holds that a new style of education is necessary ‘that will fuse religious and scientific knowledge together with morality and spirituality, to produce genuinely enlightened people with hearts illumined by religious sciences and spirituality, [and] minds illuminated with positive sciences’, people whose actions and life-styles embody humanity and moral values, and who are ‘cognizant of the socio-economic and political conditions of their time’.[71]

Michel argues that for Gülen ‘spirituality’ includes not only directly religious teachings, but also ethics, logic, psychological health, and affective openness – compassion and tolerance are key terms. Gülen believes that ‘non-quantifiable’ qualities need to be instilled in students alongside training in the ‘exact’ disciplines. Michel considers that such a program is more related to identity and daily life than ‘political action’, and believes that it will yield a new spiritual search and moral commitment to a better and more human social life. Those dimensions of education can only be conveyed through example in the teachers’ manners, disposition and behavior, not through preaching: The Gülen Movement does not dictate the curriculum in the educational institutions its participants sponsor and manage. The institutions follow national and international curricula and students are encouraged to use external sources of information, such as the internet and the universities’ information services.

The Gülen Movement, as we said, does not follow (as some cults do) an anachronistic paradigm. It does not romanticize the past. Yet it does emphasize ‘cultural values’. Gülen has said: ‘Little attention and importance is given to the teaching of cultural values, although it is more necessary to education. If one day we are able to ensure that it is given importance, then we shall have reached a major objective.’ Predictably, this emphasis has been seized upon by protectionist critics as a reactionary call to return to pre-Republican Ottoman society – in sociological terms, a kind of regressive utopianism. The term of abuse employed – irticaci – might well be translated in the Turkish context as ‘reactionary’.[72] Gülen has always denied this accusation:

The word irtica means returning to the past or carrying the past to the present. I’m a person who’s taken eternity as a goal, not only tomorrow. I’m thinking about our country’s future and trying to do what I can about it. I’ve never had anything to do with taking my country backwards in any of my writings, spoken words or activities. But no one can label belief in God, worship, moral values and […] matters unlimited by time as irtica.

Melucci has explained how some movements, at their inception, define their identity in terms of the past, drawing upon a totalizing myth of rebirth with a quasi-religious content; their action involves a utopian appeal with religious connotations. This regressive utopianism reduces complexity to the unity of a single all-embracing formula; it refuses different levels and tools of analysis, and identifies the whole society with the sacral solidarity of the group. It translates the re-appropriation of identity into the language and symbols of an escapist myth of rebirth. Melucci adds that the predominant religious accent in these movements makes them susceptible to manipulation by the power structure, to marginalization as sects, and to transformation into a fashion or commodity for sale in the marketplace as a mindsoother. He further argues that contestation in such movements changes into an individual flight, a mythical quest or fanatic fundamentalism.[73]

Other theorists have called that description an over-generalization. Sociologist Asef Bayat points to the reductionism in Melucci’s account, which considers all religious or revivalist movements, especially Islamist, as regressive utopianism.[74] For sure, it is not a description that can fit the Gülen Movement. Gülen’s references to history contain no hint of a cultural politics, no attempt to disparage any historical epoch, especially not those moments associated with the origins of modernity in Turkey.[75] He does not evoke a past so as to express a wish to restore sultanate as a symbolic shortcut to unity and order, nor does he idealize ‘homeland’, ‘religion’, and ‘family’. He is not seeking any ideological alibi to mask deficiencies in his understanding of the complexities of the modern world. Michel is very clear that Gülen does not propose ‘a nostalgic return to Ottoman patterns’.[76]

To the contrary, since the inception of the Gülen Movement, Fethullah Gülen has aspired to present models for self-improvement leading to social transformation.[77] He neither sees the past as a strategy for reinforcement of the present political order, nor considers that a new model based upon the past can or should be reinstated in the present. He has called that a grotesque anachronism, given that no sane person could believe that such a jump in time could come to fruition. He sees it as impossible for Turkey to recover the transnational hegemony it exercised before the First World War. The very idea of such cultural imperialism is incompatible with current economic, military and geographical realities. Michel observes: ‘This is very different from reactionary projects which seek to revive or restore the past. […] Gülen repeatedly affirms that “If there is no adaptation to new conditions, the result will be extinction”.’[78]

Fethullah Gülen looks to the past for examples to follow and mistakes to avoid, that is, for the means to go beyond what has remained in the past:

Today, it is obviously impossible to live with out-of-date conceptions which have nothing to do with reality. Continuing the old state being impossible, it means either following the new state or annihilation. We will either reshape our world as required by science, or we shall be thrown into a pit together with the world we live in.[79]

Nevertheless, ‘If keeping your eyes closed to the future is blindness, then disinterest in the past is misfortune.’[80] Historical consciousness clarifies the concepts of the present that are mostly shaped by the concepts and the events of the past. By presenting a very broad range of historical themes and characters, Gülen instills hope and creates access for his audience to necessary measures for reform and advance in globalized society. To him, knowing history is a feeder to an innovative and successful future in which you are able to know where you are going.

Fethullah Gülen emphatically refuses the model of citizenship that reflects a certain kind of racial, ethnic, cultural and religious homogeneity based on some (often imaginary) society in the past. In point of fact, none of the seventeen states that the Turks historically established were based on any such homogeneity. Consoling oneself with re-telling the heroic deeds of others indicates a psychological weakness peculiar to the impotent who have failed or are refusing to shoulder their present responsibilities to the present society:

Of course, we should certainly commemorate the saints of our past with deep emotion and celebrate the victories of our heroic ancestors with enthusiasm. But we should not think this is all we are obliged to do, just consoling ourselves with tombs and epitaphs. […] Each scene from the past is valuable and sacred only so long as it stimulates and enthuses us, and provides us with knowledge and experience for doing something today. Otherwise it is a complete deception, since no success or victory from the past can come to help us in our current struggle. Today, our duty is to offer humanity a new message composed of vivid scenes from the past together with understanding of the needs of the present.

For the Gülen Movement identity is not something imposed by belonging and membership in a group; it is brought into being, constructed, by the individual in her or his capacity as a social actor. It is always in accord with social capacity. Relationship is formed at the level of the single individual, and awakens the enthusiasm and capacity of the individual for action. Through sociability people rediscover the self and the meaning of life. The altruistic service urged by the Gülen Movement is this effort of human sociability and relationship. Therein lies the core of the distinctiveness of the Gülen Movement. It does not lead to a flight into the myth of identity. It does not draw an individual into an escapist illusion so that he or she is magically freed from the constraints of social action or behavior. It reaffirms the meaning of social action as the capacity for a consciously produced human existence and relationships.

In the same vein, Gülen frequently talks about a renaissance, yet he does not mean by it any sort of magical ‘rebirth’.[81] On the contrary, this renaissance is an active process, a toil – to ‘prevent illnesses like passion, laziness, seeking fame, selfishness, worldliness, narrow-mindedness, the use of brute force’ and to replace them ‘with exalted human values like contentedness, courage, modesty, altruism, knowledge and virtue, and the ability to think universally’.[82] Acknowledgement of differences, multiplicity, the necessity of division of labor, and power relationships within the larger community, attach the Gülen Movement to a form of rationality geared to assessing the relationship between ends and means, to protecting people from the imbalances and divisions created by the forms of power required to govern complexity. ‘Fethullah Gülen’s work is a constant exhortation to greater effort, greater knowledge, greater self-control and restraint.’[83]

Sects, by contrast, resist accepting difference and diversity within themselves and resist accepting their interdependence with the outside world. They lack a solution for handling difference within complexity. Their totalizing appeal does not take into account that people are simultaneously living in a system interdependently.[84] The Gülen Movement does not deny the interdependence of the social field in its worldview, values, or actual organizational frame. It does not have a totalizing ideology that possesses and controls the social field; and so it does not need to identify ‘others’ or ‘outsiders’ in negative terms.

By correctly and accurately identifying the true social character of conflicts, the Gülen Movement avoids producing unpredictable forms or expressions of collective action. Being socially, culturally and intellectually competent, Movement participants respond to the specificity of individual and collective demands, without allowing them to cancel one another out. They do not seek escape into a reductionism that ignores or annuls the individual for the appropriated identity of the movement. Utilizing this social capacity, it does not lapse into the pre-social, or withdraw into a sect or dissolve into a utopian myth. Gülen himself has said, in reference to being or becoming a sect, that he is ‘personally not in favor of such practice’, that Movement participants ‘do not represent a separate and divisive group in society’, and they ‘are not associated with any group, nor have developed such a group’.[85]

The Gülen Movement is different from a sect in that it operates in awareness of its commitment to the social field where it belongs, interacts and contributes. It shares with the rest of the society a set of general issues, and seeks to find and form common grounds and references with others. Gülen writes:

Gigantic developments in transportation and telecommunication technology have made the world into a big village. In these circumstances, all the peoples of the world must learn to share this village among them and live together in peace and mutual helping. We believe that peoples, no matter of what faith, culture, civilization, race, color and country, have more to compel them to come together than what separates them. If we encourage those elements which oblige them to live together in peace and awaken them to the lethal dangers of warring and conflicts, the world may be better than it is today.[86]

A sect by contrast simply breaks any such connection. It creates (ideologically and ontologically) separations, divisions and ruptures that cannot be overcome. Its identity politics and appeal tend to cover up or deny the fundamental dilemma of living a social life in complex systems.[87] Being an exclusive organization, a sect demands a long novitiate, rigid discipline, high level of unquestioning commitment and intrusion into every aspect of its members’ lives.[88] The worldview or collective action of the Gülen Movement is not an isolationist withdrawal into a pure community-based or sectlike structure:

We should know how to be ourselves and then remain ourselves. That does not mean isolation from others. It means preservation of our essential identity among others, following our way among other ways. While self-identity is necessary, we should also find the ways to a universal integration. Isolation from the world will eventually result in annihilation.[89]

If the search for fulfillment within specific closed networks or a society is unable to handle information flow, it withdraws from social life and transforms spiritual needs into intolerant mysticism. A movement’s identity claims pushed too far eventually evolve into a conflictual sectarian organization with an intolerant ideology, so that the movement tends to fragment into self-assertive and closed sects. If certain issues or differences become political and contradictory, and if the political decision-making is limited and incapable of resolving the differences, the movement breaks up into sectarian groupings.

However, the Gülen Movement with its participation in the field of education, interfaith and intercultural issues, and of transnational altruistic projects and institutions, proves itself able to process information and emergent realities. Interviewee Aymaz explained how this works:

The Gülen Movement acknowledges the fact that the common points, grounds, references and problems affecting humanity in general are far more than the differences which separate us. Gülen teaches that ‘one can be for others while being oneself ’, and ‘in order for a peaceful coexistence, one can build oneself among others, in togetherness with others’. The difference and particularism of an actor do not negate interdependence and unity with others. People can come together and co-operate around a universally acknowledged set of values. The way to do so is through education, convincing argument, peaceful interaction and negotiation.[90]

Aymaz emphasized that the Gülen Movement does not engage with identity politics. It does not seek to be different from other people, ethnoreligiously, culturally or geographically. Movement participants accept and abide by Turkish and international norms, regulations and laws. They share the concerns and problems common to people all over the world, and work to contribute to their resolution. The worldview, intentions and efforts of the Gülen Movement are accepted and approved by the overwhelming majority of people in Turkey and by those who know their efforts outside Turkey. It is therefore able to become an agent of reconciliation between diverse communities around the world. These efforts are actualized through legal, formalized and institutionalized means and ends. The Gülen Movement is defined in terms of its social and multicultural relations; the intention of seeking consensus among communities legitimates its transnational projects, so that it does not deviate into, or let others be led astray into, fundamentalism and sectarianism.[91]

Interviewee Ergene also argued that the Gülen Movement does not reduce reality to a small package of truisms. The service-networks are well aware of their capacity so they do not attempt to mask anything from the larger environment. The openness and transparency of its projects make the Gülen Movement effective and strengthen the confidence in it. The spirit of cultural innovation and the true spiritual seeking, alongside other faith-community members, within one’s faith strengthens one’s own sense of security and offers it to others. Interviewee Çapan made the point that, because the Gülen Movement responds to the need for cultural and social innovation, the collective search and engagement for worldly and other-worldly well-being within the Gülen Movement does not assume the character of a flight into militancy or sectarianism. Moreover, ‘in over forty years there has been no case or accusation of crisis, greed, a different theology or drug use and suicide within the Gülen Movement’. The reason for this, Çapan explained, is that people do not experience frustration, isolation, disappointment and exploitation within the Gülen Movement; quite the contrary, they feel and find hope, a true human and humane identity, communication, compassion and peace.[92]

Finally, on the question of the Gülen Movement’s charismatic leader, Ergene affirmed: ‘Though everyone who knows and comes into contact with Gülen acknowledges and respects Gülen’s knowledge, asceticism, piety, expertise and scholarliness on religious, spiritual and intellectual matters, this does not result in any sacral recognition or charisma for Gülen.’ The common description of Fethullah Gülen as the leader of the Gülen Movement – something that the man himself has never accepted or approved – has not resulted in the emergence of an authoritarian personality or personalities. The Gülen Movement has remained committed to the establishment of collective reasoning, consultation and consensus, which prevents the emergence of or lapse into herd mentality or ‘group-think’.[93]

1.4. Is the Gülen Movement a political movement?

Emergent movements in complex societies – movements of all kinds: youth, women, urban, ecological, pacifist, ethnic, cultural – have been interpreted in basically two ways: (1) in terms of an economic crisis; or (2) as a result of deficiencies in political legitimation, that is, exclusion from institutions and access to decision-making.[94] Movements are studied and understood insofar as they are mobilizing against the authoritarianism of a system, struggling for equalization of rights, seeking inclusion in the system and political recognition, or reviving ethnic or religious accents in expressions of identity or behavior considered odd or bizarre by the prevailing social order. Those who would justify that social order then interpret the movements in ideological terms – that is, as a struggle (actually or potentially) to subvert or undermine that same order. This may cause a crisis in the day-to-day fabric of social life, a breakdown in norms, loss of identity and reactive violent behavior. However, not all forms of marginalization, reactions to crises, or efforts to adapt to imbalances necessarily generate a collective action or movement, and not all collective demands assume a political form.[95]

I argued in Chapter 1 that the dominant explanation for collective action and social movements hinges largely upon a particular understanding of the European New Left action and ideology in France, Germany, and Italy after the ‘68 generation and in the 1970s.[96] As a result of the closedness of political institutions, the radicalization of movements, the prevalence of sectarian Marxist organization in the New Left, and even the lamentable turn towards terrorism, the intellectuals of the Left, as the social movement theorists, preached revolutionary ideologies. They dignified social disorder and disruptive behavior with a revolutionary label. They often based their understanding on a reductionist analysis which tended to mask some of the features of collective action. They overlooked the presence of non-political elements in emergent movements. To them, that which was not directly political in nature was folklore and private escapism and only political representation could prevent collective demands from being dissipated into such.[97]

This arbitrary ‘politicization’ of demands constitute a reductionist interpretation in that it underestimated the specificity of the emergent movements. It channeled all collective demands within its scope into rigid forms of political organization of a Leninist type. Emergent collective phenomena in complex societies cannot be treated simply as reactions to crises, as mere effects of marginality or deviance, or purely as problems arising from exclusion from the political market. In reality social movements in complex societies share a number of prominent features as multi-form and diverse as are the areas of social life. The issues are not all objectives of low negotiability, nor are they entirely reducible to political mediation. Indeed, only a portion of collective demands can be mediated and institutionalized through the functions of political representation and decision-making. Demands can re-emerge in other sectors of society, the implications of which are often outside the official channels of representation, rationalization and control by the co-ordinated intervention of state apparatuses.[98]

Also in chapter 1, and again in 3, I pointed to a striking phenomenon in recent forms of collective action, namely that they ‘largely ignore the political system. They generally display disinterest towards the idea of seizing power’.[99] New social movements are less engaged with social and political conflict than before because ‘collective bargaining, party competition, and representative party government were the virtually exclusive mechanisms for the resolution of social and political conflict. All of this was endorsed by a “civic culture” which emphasized the values of social mobility, private life, consumption, instrumental rationality, authority, and order and which de-emphasized political participation’.[100] New social movements are, instead, characterized by open and fluid organization, inclusive and non-ideological participation, and greater attention to social than to economic transformations.[101]

All of this raises questions about the relationship between the Gülen Movement and the political system in Turkey. For, as argued in earlier chapters and in §4.1.2 above, a notable feature of the Gülen Movement is that participants acknowledge and abide by the political system, and display disinterest towards seizing power and gaining control over the state apparatus. The Gülen Movement assumes forms of action and organization which are accountable and amenable to political mediation by the Turkish political system, without becoming identifiable with it. The Gülen Movement therefore does not act like an oppositional action which involves a minority, or which rejects the system in Turkey, or which resists the ‘rationality’ of decisions and goals imposed by the Turkish system.

To a certain extent, within different contexts and in response to different questions, the arguments have established that the Gülen Movement is what Melucci would call a cultural actor, or a social, not a political, movement. So, from here on, the discussion will focus on how the Gülen Movement as collective actor and its action are different from a political party, and the implications for Turkey, democracy, Islamism, subterfuge and dissembling, development or change in Turkey, and Turkey’s integration into the international community.

The chief implication of the Gülen Movement is that political parties are unable to give adequate expression to collective demands. This is because parties are structured to represent interests that are assumed to remain relatively stable, with a distinct geographical, occupational, social, or ideological base. Also, a party must ensure the continuity of the interests it represents. When faced with the task of representing a plurality of interests, the traditional structure of a party may not be able to adjust itself to accommodate them. Indeed, it can hardly mediate between short- and longterm goals. For short-term gains and profits a party may act in favor of unstable, partial and hierarchical interests. In contrast, unlike political parties and bodies, the Gülen Movement’s participation in social projects and in the specific areas of social life demonstrates no interest in hierarchism or short-term gains.

Moreover, the Gülen Movement represents its understanding through formal and institutionalized SMOs. As these institutions are mostly educational they do not take sides with political parties. Rather than being distant to some, Gülen says, they are equally near to all.